Imagining Covid under a normal president.

This week I had a conversation that left a mark. It was with Mary Louise Kelly and E.J. Dionne on NPR’s “All Things Considered,” and it was about how past presidents had handled moments of national mourning — Lincoln after Gettysburg, Reagan after the Challenger explosion and Obama after the Sandy Hook school shootings.

The conversation left me wondering what America’s experience of the pandemic would be like if we had a real leader in the White House.

If we had a real leader, he would have realized that tragedies like 100,000 Covid-19 deaths touch something deeper than politics: They touch our shared vulnerability and our profound and natural sympathy for one another.

In such moments, a real leader steps outside of his political role and reveals himself uncloaked and humbled, as someone who can draw on his own pains and simply be present with others as one sufferer among a common sea of sufferers.

If we had a real leader, she would speak of the dead not as a faceless mass but as individual persons, each seen in unique dignity. Such a leader would draw on the common sources of our civilization, the stores of wisdom that bring collective strength in hard times.

Lincoln went back to the old biblical cadences to comfort a nation. After the church shooting in Charleston, Barack Obama went to “Amazing Grace,” the old abolitionist anthem that has wafted down through the long history of African-American suffering and redemption.

In his impromptu remarks right after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy recalled the slaying of his own brother and quoted Aeschylus: “In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

If we had a real leader, he would be bracingly honest about how bad things are, like Churchill after the fall of Europe. He would have stored in his upbringing the understanding that hard times are the making of character, a revelation of character and a test of character. He would offer up the reality that to be an American is both a gift and a task. Every generation faces its own apocalypse, and, of course, we will live up to our moment just as our ancestors did theirs.

If we had a real leader, she would remind us of our common covenants and our common purposes. America is a diverse country joined more by a common future than by common pasts. In times of hardships real leaders re-articulate the purpose of America, why we endure these hardships and what good we will make out of them.

After the Challenger explosion, Reagan reminded us that we are a nation of explorers and that the explorations at the frontiers of science would go on, thanks in part to those who “slipped the surly bonds of earth to touch the face of God.”

At Gettysburg, Lincoln crisply described why the fallen had sacrificed their lives — to show that a nation “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” can long endure and also to bring about “a new birth of freedom” for all the world.

Of course, right now we don’t have a real leader. We have Donald Trump, a man who can’t fathom empathy or express empathy, who can’t laugh or cry, love or be loved — a damaged narcissist who is unable to see the true existence of other human beings except insofar as they are good or bad for himself.

But it’s too easy to offload all blame on Trump. Trump’s problem is not only that he’s emotionally damaged; it is that he is unlettered. He has no literary, spiritual or historical resources to draw upon in a crisis.

All the leaders I have quoted above were educated under a curriculum that put character formation at the absolute center of education. They were trained by people who assumed that life would throw up hard and unexpected tests, and it was the job of a school, as one headmaster put it, to produce young people who would be “acceptable at a dance, invaluable in a shipwreck.”

Think of the generations of religious and civic missionaries, like Frances Perkins, who flowed out of Mount Holyoke. Think of all the Morehouse Men and Spelman Women. Think of all the young students, in schools everywhere, assigned Plutarch and Thucydides, Isaiah and Frederick Douglass — the great lessons from the past on how to lead, endure, triumph or fail. Only the great books stay in the mind for decades and serve as storehouses of wisdom when hard times come.

Right now, science and the humanities should be in lock step: science producing vaccines, with the humanities stocking leaders and citizens with the capacities of resilience, care and collaboration until they come. But, instead, the humanities are in crisis at the exact moment history is revealing how vital moral formation really is.

One of the lessons of this crisis is that help isn’t coming from some centralized place at the top of society. If you want real leadership, look around you.

Dave Ramsey: Leaders Eat Last

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/7ldH7mTUe9M?start=360″ frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>06:00went off on a rabbit hole but anyway theleaders the first thing that’s going tohappen in this in this organization isthe Ramseys will not get paid our nameson the building that’s the first thingthat will happen before I lay is soldoff and the second thing will happen isour leaders in the operating board arenot going to get paid and by the waythey’re all okay with that and the thirdthing that will happen is we’ve had awhole bunch of volunteers at the nextlevel down that of leadership that saysI’m okay I can make it for 30 days alsoget a paycheck too if it means we don’thave to lay people off those are realleaders they’re putting themselves aheadthey’re putting their team I had theteam’s good ahead of themselvesleadership generally sucks you’reconstantly having make bad decisionswith I mean make good decisions with badinformation and partial knowledge ofwhat’s going on and you got to make thecallanyway it’s high-stress people’sfeelings are involved and no oneappreciates it but you got to do itanyway that’s what leadership is theleadership is going first on the hardthings if you don’t go you’re not you’renot leading it’s not going first on theupside it’s going first on the downsideand assuming the risk and absorbing thatso the team doesn’t have to right Kenyeah well I think a lot of people takingthese loans are following everybody elsewell everybody else is doing I’m gonnado it again let’s break this thing aboutmy finesse my planner who makes lessthan I make is advising me right myaccountant who you know does not hasnever made a payroll in his life exceptis one secretary is advising me on howto run this business no no absolutelynotdo not take these loans out yeah you’regoing to create problems that you don’tsee yet a hundred percent chance of thatyou don’t have to be a rocket scientistto figure this out as my buddy LarryChapman says it ain’t rocket surgery soI mean it’s just you know guys pleaseplease there’s two problems here one isis that you’re counting on debt to beyour supplier you’re your provider thesecond thing is you’re waiting on thegovernment to be your provider neitherone of these turn out to be goodproviders you come up with that is tocreate revenues fresh and different anddigitally in the middle of this mess godo something special and new even ifyou’re just doing it for 30 days thatyou’ve never done before and you maynever do again cut your own pay preservecache preserve cache preserve cache selloff assets and protect your peopleprotect your peoplethat’s what you do well and if we haveto furlough them you’re gonna cry whileyou do it and not take a paycheck to beclear and you said this this morning inour meeting you said at the end of theday if it came down to it after doingall that and you should do all thosethings first we would have to do layoffsbefore we take on debt on principle I’mnot one not on principle because I thinkit’s the shortest way to healing it’sthe best way to run an organizationbecause it’s the most profitable andit’s the smartest it’s the wisest avoidthe stinking debt please guys please andyou can be mad at me and you make fun ofme some dinosaur if you want but I’msitting here freaking open – so shut up

Coronavirus: A Theory of Incompetence

Leaders in the public and private sector in advanced economies, typically highly credentialed, have with very few exceptions shown abject incompetence in dealing with coronavirus as a pathogen and as a wrecker of economies. The US and UK have made particularly sorry showings, but they are not alone.

It’s become fashionable to blame the failure to have enough medical stockpiles and hospital beds and engage in aggressive enough testing and containment measures on capitalism. But as I will describe shortly, even though I am no fan of Anglosphere capitalism, I believe this focus misses the deeper roots of these failures.

After all the country lauded for its response, South Korea, is capitalist. Similarly, reader vlade points out that the Czech Republic has had only 2 coronavirus deaths per million versus 263 for Italy. Among other things, the Czech Republic closed its borders in mid-March and made masks mandatory. Newscasters and public officials wear them to underscore that no one is exempt.

Even though there are plenty of examples of capitalism gone toxic, such as hospitals and Big Pharma sticking doggedly to their price gouging ways or rampant production disruptions due to overly tightly-tuned supply chains, that isn’t an adequate explanation. Government dereliction of duty also abound. In 2006, California’s Governor Arnold Schwarznegger reacted to the avian flu by creating MASH on steroids. From the LA Times:

They were ready to roll whenever disaster struck California: three 200-bed mobile hospitals that could be deployed to the scene of a crisis on flatbed trucks and provide advanced medical care to the injured and sick within 72 hours.

Each hospital would be the size of a football field, with a surgery ward, intensive care unit and X-ray equipment. Medical response teams would also have access to a massive stockpile of emergency supplies: 50 million N95 respirators, 2,400 portable ventilators and kits to set up 21,000 additional patient beds wherever they were needed…

“In light of the pandemic flu risk, it is absolutely a critical investment,” he [Governor Schwarznegger] told a news conference. “I’m not willing to gamble with the people’s safety.”

They were dismantled in 2011 by Governor Jerry Brown as part of post-crisis belt tightening.

The US for decades has as a matter of policy tried to reduce the number of hospital beds, which among other things has led to the shuttering of hospitals, particularly in rural areas. Hero of the day, New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo pursued this agenda with vigor, as did his predecessor George Pataki.

And even though Trump has made bad decision after bad decision, from eliminating the CDC’s pandemic unit to denying the severity of the crisis and refusing to use government powers to turbo-charge state and local medical responses, people better qualified than he is have also performed disastrously. America’s failure to test early and enough can be laid squarely at the feet of the CDC. As New York Magazine pointed out on March 12:

In a functional system, much of the preparation and messaging would have been undertaken by the CDC. In this case, it chose not to simply adopt the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 test kits — stockpiling them in the millions in the months we had between the first arrival of the coronavirus in China and its widespread appearance here — but to try to develop its own test. Why? It isn’t clear. But they bungled that project, too, failing to produce a reliable test and delaying the start of any comprehensive testing program by a few critical weeks.

The testing shortage is catastrophic: It means that no one knows how bad the outbreak already is, and that we couldn’t take effectively aggressive measures even we wanted to. There are so few tests available, or so little capacity to run them, that they are being rationed for only the most obvious candidates, which practically defeats the purpose. It is not those who are very sick or who have traveled to existing hot spots abroad who are most critical to identify, but those less obvious, gray-area cases — people who may be carrying the disease around without much reason to expect they’re infecting others…Even those who are getting tested have to wait at least several days for results; in Senegal, where the per capita income is less than $3,000, they are getting results in four hours. Yesterday, apparently, the CDC conducted zero tests…

[O]ur distressingly inept response, kept bringing to mind an essay by Umair Haque, first published in 2018 and prompted primarily by the opioid crisis, about the U.S. as the world’s first rich failed state

And the Trump Administration has such difficulty shooting straight that it can’t even manage its priority of preserving the balance sheets of the well off. Its small business bailouts, which are as much about saving those enterprises as preserving their employment, are off to a shaky start. How many small and medium sized ventures can and will maintain payrolls out of available cash when they aren’t sure when and if Federal rescue money will hit their bank accounts?

How did the US, and quite a few other advanced economies, get into such a sorry state that we are lack the operational capacity to engage in effective emergency responses? Look at what the US was able to do in the stone ages of the Great Depression. As Marshall Auerback wrote of the New Deal programs:

The government hired about 60 per cent of the unemployed in public works and conservation projects that

- planted a billion trees,

- saved the whooping crane,

- modernized rural America, and

- built such diverse projects as the Cathedral of Learning in Pittsburgh,

- the Montana state capitol,

- much of the Chicago lakefront,

- New York’s Lincoln Tunnel and Triborough Bridge complex,

- the Tennessee Valley Authority and

- the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Yorktown. It also

- built or renovated 2,500 hospitals,

- 45,000 schools,

- 13,000 parks and playgrounds,

- 7,800 bridges,

- 700,000 miles of roads, and

- a thousand airfields. And it

- employed 50,000 teachers,

- rebuilt the country’s entire rural school system, and

- hired 3,000 writers,

- musicians,

- sculptors and painters,

- including Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

What are the deeper causes of our contemporary generalized inability to respond to large-scale threats? My top picks are a lack of respect for risk and the rise of symbol manipulation as the dominant means of managing in the private sector and government.

Risk? What Risk?

Thomas Hobbes argued that life apart from society would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” Outside poor countries and communities, advances in science and industrialization have largely proven him right.

It was not long ago, in historical terms, that even aristocrats would lose children to accidents and disease. Only four of Winston Churchill’s six offspring lived to be adults. Comparatively few women now die in childbirth.

But it isn’t just that better hygiene, antibiotics, and vaccines have helped reduce the scourges of youth. They have also reduced the consequences of bad fortune. Fewer soldiers are killed in wars. More are patched up, so fewer come back in coffins and more with prosthetics or PTSD. And those prosthetics, which enable the injured to regain some of their former function, also perversely shield ordinary citizens from the spectacle of lost limbs.1

Similarly, when someone is hit by a car or has a heart attack, as traumatic as the spectacle might be to onlookers, typically an ambulance arrives quickly and the victim is whisked away. Onlookers can tell themselves he’s in good hands and hope for the best.

With the decline in manufacturing, fewer people see or hear of industrial accidents, like the time a salesman in a paper mill in which my father worked stuck his hand in a digester and had his arm ripped off. And many of the victims of hazardous work environments suffer from ongoing exposures, such as to toxic chemicals or repetitive stress injuries, so the danger isn’t evident until it is too late.

Most also are oddly disconnected from the risks they routinely take, like riding in a car (I for one am pretty tense and vigilant when I drive on freeways, despite like to speed as much as most Americans). Perhaps it is due in part to the illusion of being in control while driving.

Similarly, until the coronavirus crisis, even with America’s frayed social safety nets, most people, particularly the comfortably middle class and affluent, took comfort in appearances of normalcy and abundance. Stores are stocked with food. Unlike the oil crisis of the 1970, there’s no worry about getting petrol at the pump. Malls may be emptying out and urban retail vacancies might be increasing, but that’s supposedly due to the march of Amazon, and not anything amiss with the economy. After all, unemployment is at record lows, right?

Those who do go to college in America get a plush experience. No thin mattresses or only adequately kept-up dorms, as in my day. The notion that kids, even of a certain class, have to rough it a bit, earn their way up and become established in their careers and financially, seems to have eroded. Quite a few go from pampered internships to fast-track jobs. In the remote era of my youth, even in the prestigious firms, new hires were subjected to at least a couple of years of grunt work.

So the class of people with steady jobs (which these days are well-placed members of the professional managerial class, certain trades and those who chose low-risk employment with strong civil service protections) have also become somewhat to very removed from the risks endured when most people were subsistence farmers or small town merchants who served them.

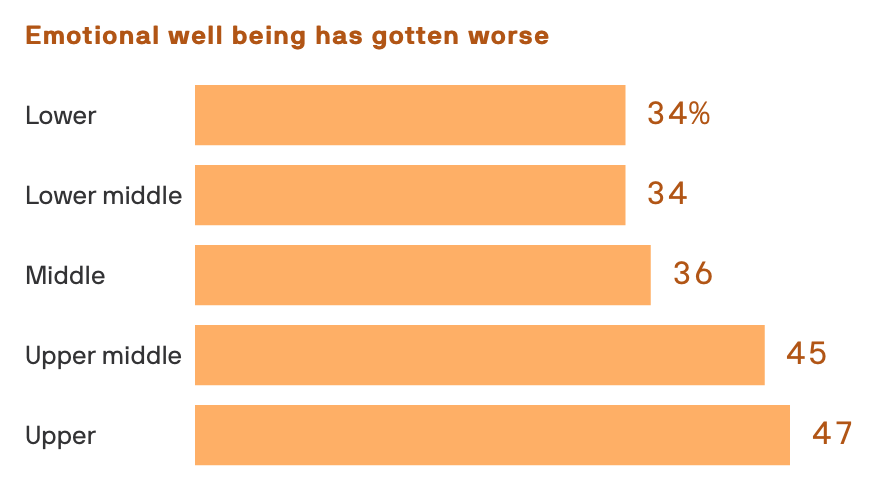

Consider this disconnect, based on an Axios-Ipsos survey:

The coronavirus is spreading a dangerous strain of inequality. Better-off Americans are still getting paid and are free to work from home, while the poor are either forced to risk going out to work or lose their jobs.

Generally speaking, the people who are positioned to be least affected by coronavirus are the most rattled. That is due to the gap between expectations and the new reality. Poor people have Bad Shit Happen on a regular basis. Wealthy people expect to be able to insulate themselves from most of it and then have it appear in predictable forms, like cheating spouses and costly divorces, bad investments (still supposedly manageable if you are diversified!), renegade children, and common ailments, like heart attacks and cancer, where the rich better the odds by advantaged access to care.

The super rich are now bunkered, belatedly realizing they can’t set up ICUs at home, and hiring guards to protect themselves from marauding hordes, yet uncertain that their mercenaries won’t turn on them.

The bigger point is that we’ve had a Minksy-like process operating on a society-wide basis: as daily risks have declined, most people have blinded themselves to what risk amounts to and where it might surface in particularly nasty forms. And the more affluent and educated classes, who disproportionately constitute our decision-makers, have generally been the most removed.

The proximity to risk goes a long way to explaining who has responded better. As many have pointed out, the countries that had meaningful experience with SARS2 had a much better idea of what they were up against with the coronavirus and took aggressive measures faster.

But how do you explain South Korea, which had only three cases of SARS and no deaths? It doesn’t appear to have had enough experience with SARS to have learned from it.

A related factor may be that developing economies have fresh memories of what life was like before they became affluent. I can’t speak for South Korea, but when I worked with the Japanese, people still remembered the “starving times” right after World War II. Japan was still a poor country in the 1960s.3 South Korea rose as an economic power after Japan. The Asian Tigers were also knocked back on their heels with the 1997 emerging markets crisis. And of course Seoul is in easy nuke range of North Korea. It’s the only country I ever visited, including Israel, where I went through a metal detector to enter and saw lots of soldiers carrying machine guns in the airport. So they likely have a keen appreciation of how bad bad can be.

The Rise and Rise of the Symbol Economy

Let me start with an observation by Peter Drucker that I read back in the 1980s, but will then redefine his take on “symbol economy,” because I believe the phenomenon has become much more pervasive than he envisioned.

A good recap comes in Fragile Finance: Debt, Speculation and Crisis in the Age of Global Credit by A. Nesvetailova:

The most significant transformation for Drucker was the changed relationship between the symbolic economy of capital movements, exchange rates, and credit flows, and the real economy of the flow of goods and services:

…in the world economy of today, the ‘real economy’ of goods and services and the ‘symbol economy’ of money, credit, and capital are no longer bound tightly to each other; they are indeed, moving further and further apart (1986: 783)

The rise of the financial sphere as the flywheel of the world economy, Drucker noted, is both the most visible and the least understood change of modern capitalism.

What Drucker may not have sufficiently appreciated was money and capital flows are speculative and became more so over time. In their study of 800 years of financial crises, Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff found that high levels of international capital flows were strongly correlated with more frequent and more severe financial crises. Claudio Borio and Petit Disyatat of the Banks of International Settlements found that on the eve of the 2008 crisis, international capital flows were 61 times as large as trade flows, meaning they were only trivially settling real economy transactions.

Now those factoids alone may seem to offer significant support to Drucker’s thesis. But I believe he conceived of it too narrowly. I believe that modeling techniques, above all, spreadsheet-based models, have removed decision-makers from the reality of their decisions. If they can make it work on paper, they believe it will work that way.

When I went to business school and started on Wall Street, financiers and business analysts did their analysis by hand, copying information from documents and performing computations with calculators. It was painful to generate financial forecasts, since one error meant that everything to the right was incorrect and had to be redone.

The effect was that when managers investigated major capital investments and acquisitions, they thought hard about the scenarios they wanted to consider since they could look at only a few. And if a model turned out an unfavorable-looking result, that would be hard to rationalize away, since a lot of energy had been devoted to setting it up.

By contrast, when PCs and Visicalc hit the scene, it suddenly became easy to run lots of forecasts. No one had any big investment in any outcome. And spending so much time playing with financial models would lead most participants to a decision to see the model as real, when it was a menu, not a meal.

When reader speak with well-deserved contempt of MBA managers, the too-common belief that it is possible to run an operation, any operation, by numbers, appears to be a root cause. For over five years, we’ve been running articles from the Health Renewal Blog decrying the rise of “generic managers” in hospital systems (who are typically also spectacularly overpaid) who proceed to grossly mismanage their operations yet still rake in the big bucks.

The UK version of this pathology is more extreme, because it marries managerial overconfidence with a predisposition among British elites to look at people who work hard as “must not be sharp.” But the broad outlines apply here. From Clive, on a Brexit post, when Brexit was the poster child of UK elite incompetence:

What’s struck me most about the UK government’s approach to the practical day-to-day aspects of Brexit is that it is exemplifying a typically British form of managerialism which bedevilles both public sector and private sector organisations. It manifests itself in all manner of guises but the main characteristic is that some “leader” issues impractical, unworkable, unachievable or contradictory instructions (or a “strategy”) to the lower ranks. These lower ranks have been encouraged to adopt the demeanour of yes-men (or yes-women). So you’re not allowed to question the merits of the ask. Everyone keeps quiet and takes the paycheck while waiting for the roof to fall in on them. It’s not like you’re on the breadline, so getting another year or so in isn’t a bad survival attitude. If you make a fuss now, you’ll likely be replaced by someone who, in the leadership’s eyes is a lot more can-do (but is in fact just either more naive or a better huckster).

Best illustrated perhaps by an example — I was asked a day or two ago to resolve an issue I’d reported using “imaginative” solutions. Now, I’ve got a a vivid imagination, but even that would not be able to comply with two mutually contradictory aims at the same time (“don’t incur any costs for doing some work” and “do the work” — where because we’ve outsourced the supply of the services in question, we now get real, unhideable invoices which must be paid).

To the big cheeses, the problem is with the underlings not being sufficiently clever or inventive. The real problem is the dynamic they’ve created and their inability to perceive the changes (in the same way as swinging a wrecking ball is a “change”) they’ve wrought on an organisation.

May, Davies, Fox, the whole lousy lot of ’em are like the pilot in the Airplane movie — they’re pulling on the levers of power only to find they’re not actually connected to anything. Wait until they pull a little harder and the whole bloody thing comes off in their hands.

Americans typically do this sort of thing with a better look: the expectations are usually less obviously implausible, particularly if they might be presented to the wider world. One of the cancers of our society is the belief that any problem can be solved with better PR, another manifestation of symbol economy thinking.

I could elaborate further on how these attitudes have become common, such as the ability of companies to hide bad operating results and them come clean every so often as if it were an extraordinary event, short job tenures promoting “IBG/YBG” opportunism, and the use of lawyers as liability shields (for the execs, not the company, natch).

But it’s not hard to see how it was easy to rationalize away the risks of decisions like globalization. Why say no to what amounted to a transfer from direct factory labor to managers and execs? Offshoring and outsourcing were was sophisticated companies did. Wall Street liked them. Them gave senior employees an excuse to fly abroad on the company dime. So what if the economic case was marginal? So what if the downside could be really bad? What Keynes said about banker herd mentality applies:

A sound banker, alas! is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional and orthodox way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.

It’s not hard to see how a widespread societal disconnect of decision-makers from risk, particularly health-related risks, compounded with management by numbers as opposed to kicking the tires, would combine to produce lax attitude toward operations in general.

I believe a third likely factor is poor governance practices, and those have gotten generally worse as organizations have grown in scale and scope. But there is more country-specific nuance here, and I can discuss only a few well, so adding this to my theory will have to hold for another day. But it isn’t hard to think of some in America. For instance, 40 years ago, there were more midsized companies, with headquarters in secondary cities like Dayton, Ohio. Executives living in and caring about their reputation in their communities served as a check on behavior.

Before you depict me as exaggerating about the change in posture toward risks, I recall reading policy articles in the 1960s where officials wrung their hands about US dependence on strategic materials found only in unstable parts of Africa. That US would never have had China make its soldiers’ uniforms, boots, and serve as the source for 80+ of the active ingredients in its drugs. And America was most decidedly capitalist in the 1960s. So we need to look at how things have changed to explain changes in postures towards risk and notions of what competence amounts to.

_____

1 One of my early memories was seeing a one-legged man using a crutch, with the trouser of his missing leg pinned up. I pointed to him and said something to my parents and was firmly told never to do anything like that again.2 The US did not learn much from its 33 cases. But the lack of fatalities may have contributed.

3 Japan has had a pretty lame coronavirus response, but that is the result of Japan’s strong and idiosyncratic culture. While Japanese are capable of taking action individually when they are isolated, in group settings, no one wants to act or even worse take responsibility unless their is an accepted or established protocol.

The S.E.C. Rule That Destroyed The Universe

How the coronavirus is creating a political opportunity to overturn one of the worst practices of the kleptocracy era

The Covid-19 crisis has revealed gruesome core dysfunction.

- Drug companies have to be bribed to make needed medicines,

- state governments improvise harebrained plans for emergency elections, and

- industrial capacity has been offshored to the point where making enough masks seems beyond the greatest country in the world.

But the biggest shock involves the economy. How were we this vulnerable to disruption? Why do industries like airlines that just minutes ago were bragging about limitless profitability – American CEO Doug Parker a few years back insisted, “My personal view is that you won’t see losses in the industry at all” – suddenly need billions? Where the hell did the money go?

In Washington, everyone from Donald Trump to Joe Biden to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is suddenly pointing the finger at stock buybacks, a term many Americans are hearing for the first time.

This breaks a taboo of nearly forty years, during which politicians in both parties mostly kept silent about a form of legalized embezzlement and stock manipulation, greased by an obscure 1982 rule implemented by Ronald Reagan’s S.E.C., that devoured trillions of national wealth.

The mechanics of buybacks are simple. Companies buy their own stock and retire the shares, increasing the value of shares remaining in circulation. This translates into instant windfalls for shareholders and executives that approve the purchases. That this should be proscribed as market manipulation, and additionally offers a clear path to insider trading – former SEC chief Rob Jackson found corporate insiders were five times as likely to sell stock after a share repurchase was announced – is just one problem.

The worse problem comes when companies not only spend all of their available resources on stock distributions, but borrow to fund even more distributions. This leaves companies with razor-thin margins of error, quickly exposed in a crisis like the current one.

“When companies spend billions on buybacks, they’re not spending it on research and development, on plant expansion, on employee benefits,” says Dennis Kelleher of Better Markets. “Corporations are loaded up with debt they wouldn’t otherwise have. They’re intentionally deciding to live on the very edge of calamity to benefit the richest Americans.”

It’s hard to overstate how much money has vanished. S&P 500 companies overall spent the size of the recent bailout – $2 trillion – on buybacks just in the last three years!

Banks spent $155 billion on buybacks and dividends across a 12-month period in 2019-2020. As former FDIC chief Sheila Bair pointed out last month, “as a rule of thumb $1 of capital supports $16 of lending.” So, $155 billion in buybacks and dividends translates into roughly $2.4 trillion in lending that didn’t happen.

Most all of the sectors receiving aid through the new CARES Act programs moved huge amounts to shareholders in recent years. The big four airlines – Delta, United, American, and Southwest – spent $43.7 billion on buybacks just since 2012. If that sum sounds familiar, it’s because it equals almost exactly the size of the $50 billion bailout airlines are being given as part of the CARES Act relief package.

The two major federal financial rescues, in 2008-2009 and now, have become an important part of a cover story shifting attention from all this looting: the public has been trained to think companies have been crippled by investment losses, when the biggest drain has really come via a relentless program of intentional extractions.

Corporate officers treat their own companies like mob-owned restaurants or strip mines, to be systematically pillaged for value using buybacks as the main extraction tool. During this period corporations laid off masses of workers they could afford to keep, begged for bailouts and federal subsidies they didn’t need, and issued mountains of unnecessary debt, essentially to pay for accelerated shareholder distributions.

All this was done in service of a lunatic religion of “maximizing shareholder value.” “MSV” by now has been proven a moronic canard – even onetime shareholder icon Jack Welch said ten years ago it was “the dumbest idea in the world” – and it’s had the result of promoting a generation of corporate leaders who are

- skilled at firing people,

- hustling public subsidies, and

- borrowing money to fund stock awards for themselves, but

- apparently know jack about anything else.

During a Covid-19 crisis where we need corporations to innovate and deliver life-saving goods and services, this is suddenly a major problem. “We’re seeing, these people don’t have the slightest idea of how to run their own companies,” says Harvard economist William Lazonick.

Wall Street analysts spent the last weeks mulling over the grim news that society is wondering if it can afford to keep sending most of its wealth to a handful of tax-avoidant executives and corporate raiders (known euphemistically in the 21stcentury as “activist investors”). The Sanford Bernstein research firm sent a note to clients Monday warning buybacks would be “severely curtailed” in coming years, for the “intriguing” reason that they were becoming “socially unacceptable” in this crisis period.

Goldman, Sachs chimed in with a similar observation. “Buyback activity will slow dramatically, both for political and practical reasons,” the bank told clients.

The political furor on the Hill in the last weeks has mostly been limited to grandstanding demands that recipients of aid in the $2 trillion CARES Act not be spent on stock distributions. “I’ll take it, but most of them don’t know what the hell they’re talking about,” is how one economist described these complains.

If politicians did understand the buyback issue more fully, they either wouldn’t have voted for this unanimously-approved bailout, or would have insisted on permanent bans, given the central role such extraction schemes played in necessitating the current crisis to begin with. The history is ridiculous enough.

***

The newspaper record of November 17, 1982 shows an ordinary day from the go-go Reagan years. Republicans boosted tax cuts and military budget hikes. An NFL player strike ended after 57 days. Soviet and Chinese foreign ministers met, and 80 complete skeletons were found in a dig at Mount Vesuvius in what one scientist called a “masterpiece of pathos.”

There was little news of a rule passed by the Securities and Exchange Commission and implemented with almost no documentary footprint. “It’s not written about in histories of the S.E.C.,” says Lazonick. “It’s barely mentioned even in retrospect.”

Yet rule 10b-18, which created a “safe harbor” for stock repurchases, had a radical impact. For decades before Reagan came into office and stuck E.F. Hutton executive John Shad in charge of the S.E.C. – the first time since inaugural chief Joseph Kennedy’s tenure in the thirties that a Wall Street creature had been made America’s top financial regulator – officials had tried numerous times to define insider purchases of stock as illegal market manipulation.

Again, when companies buy up their own stock, they’re artificially boosting the value of the remaining shares. The rule passed by Shad’s S.E.C. in 1982 not only didn’t define this as illegal, it laid out a series of easily-met conditions under which companies that engaged in such buybacks were free of liability. Specifically, if buybacks constituted less than 25% of average daily trading volume, they fell within the “safe harbor.”

The S.E.C. in adopting the rule emphasized the need for the government to get out of the way of such a good thing:

The Commission has recognized that issuer repurchase programs are seldom undertaken with improper intent… any rule in this area must not be overly intrusive.

The rule added that companies may be justified in “stepping out” of safe harbor guidelines, and said that there would be no presumption of misconduct if purchases were not made in compliance with 10b-18. Thirty-three years later, in 2015, S.E.C. Chief Mary Jo White would double down on this extraordinary take on “regulation,” saying that “because Rule 10b-18 is a voluntary safe harbor, issuers cannot violate the rule.”

10b-18 was a victory for a movement popularized in the late sixties by Milton Friedman and furthered in the mid-seventies by academics like Michael Jensen and Dean William Meckling. The aim was to change the core function of the American corporation. If corporate officers previously had to build value for a variety of stakeholders – customers, employees, the firm itself, society – the new idea was to narrow focus to a single variable, i.e. “maximizing shareholder value.”

Like objectivism and other greed-based religions that helped birth the modern version of corporate capitalism, “MSV” was anchored on hyper-rosy assumptions tying efficiency to self-interest. It was said CEOs paid in stock would become owners, which would lead to reductions in spending on private jets and other waste.

Shareholders previously were paid via dividends, or by waiting for share prices to appreciate and selling them. Now there was a shortcut: board members chosen by shareholders could raid their own companies’ assets to buy stock and to goose share prices.

Employees, customers, and society were suddenly in direct competition for resources with executives and shareholders. Should a company invest in a new factory, or should it just deliver instant millions to shareholders and executives paid in options?

By 1997, MSV became orthodoxy, as the Business Roundtable declared that the “paramount duty of management and of boards of directors is to the corporation’s stockholders.” This was understood to mean that the sole purpose of the corporation was to create value for shareholders.

In the 2008 financial crisis, many firms poured resources into buybacks even as they hurtled toward bankruptcy. Some kept shifting money to stock buys practically until the day of their deaths. Lehman Brothers, for instance, announced a 13% dividend increase and a $100 million share repurchase in January 2008, when the firm was already circling the drain. Many of the TARP bailout recipients kept up buybacks even during the bleakest days of the financial crisis.

“If you added up the capital distributions of the banks in just the few years before the crash,” says Kelleher, “it adds up to half the TARP. They wouldn’t have needed a bailout if they’d [curbed] distributions.”

Before and after 2008, American companies repeatedly begged to be subsidized by taxpayers even as they systematically liquidated revenues via buybacks.

For instance, as Lazonick pointed out in a 2012 paper, Intel in 2005 lobbied the U.S. government to invest in nanotechnology, warning “U.S. leadership in the nanoelectronics era is not guaranteed” and would be lost absent a “massive, coordinated research effort” that included state and federal investment. That year, Intel spent $10.5 billion on buybacks, and spent $48.3 billion on them in 2001-2010 overall, four times what the federal government ended up spending on the National Nanotechnology Initiative.

The classic extraction trifecta was to ask for public investment, take on huge debts, and enact mass layoffs as a firm spent billions on distributions.

Microsoft in 2009 laid off 5,000 workers (its first mass layoff) and did a $3.75 billion bond issue (its first long-term bond) despite earning $19 billion. That same year, the company spent $9.4 billion on buybacks and $4.5 billion on dividends. Lazonick argues such cash-rich companies borrowed money in order to avoid having to repatriate overseas profits, which would have forced them to pay taxes before blowing cash on buybacks.

Buyback waste is breathtaking. Exxon-Mobil, apparently disinterested in researching alternative energy sources, did $174 billion in buybacks between 2001-2010. The nation’s 18 largest pharmaceutical companies, who feed off NIH grants for free research and have relentlessly lobbied to be protected from generics, reimportation, the use of Medicare’s bargaining power to lower prices, spent $388 billion on buybacks in the last decade.

Apple, upon whose board sits relentless seeker-of-green-technology-seed-capital Al Gore, did $45 billion in buybacks in one year (2014) and $239 billion over a six year period between 2012 and 2018. Gore also owned over 79,000 shares of Apple as of last January, and sold nearly $40 million worth of Apple stock in February of 2017. So he’s probably not too upset that Apple is spending sums equivalent to major bailout programs on stock repurchases, rather than investing in new technologies.

In March of 2018, Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin finally introduced legislation to halt the practice, called the Reward Work Act, which would:

Ban open-market stock buybacks that overwhelmingly benefit executives and activist hedge funds at the expense of workers and retirement savers. It would also empower workers by requiring public companies to allow workers to directly elect one-third of their company’s board of directors.

In summer of 2019, the Business Roundtable shook corporate America by abandoning “shareholder value” as the animating principle of American business. This led to a spate of breathless news reports: “Shareholder Value Is No Longer Everything” (New York Times), “Group of US corporate leaders ditches shareholder-first mantra” (Financial Times) and, “Maximizing Shareholder Value is Finally Dying” (Forbes).

This was all going on against the backdrop of a Democratic presidential election campaign that in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren especially saw the rise of furious anti-corporate sentiment. The Roundtable response might have been P.R. designed to dull the pitchforks somewhat, but it’s notable that there was enough worry about the optics of shareholder piggery to even do that much.

As Forbes put it:

Maximizing shareholder value has come to be seen as leading to a toxic mix of soaring short-term corporate profits, astronomic executive pay, along with stagnant median incomes, growing inequality, periodic massive financial crashes, declining corporate life expectancy, slowing productivity, declining rates of return on assets and overall, a widening distrust in business…

Economist Lenore Palladino, who has worked on these issues for years, hopes Covid-19 and other looming crises will force politicians and the public to see fundamental changes to corporate structure as inevitable.

“I believe there will be a political mandate to ensure business resiliency in the 2020s, not only to survive coronavirus, but so that the American workforce can thrive in the era of climate change,” she says. Banning buybacks, she says, would (among other reforms) comprise “one step towards rebalancing power inside corporations.”

However, unless the public puts more pressure on politicians to keep the issue alive during the coronavirus crisis, the $2 trillion rescue and the near-daily barrage of radical new bailout facilities being introduced – the Fed as of this writing is introducing yet another amazing “bazooka” program to hoover up junk bonds – could just end up subsidizing the last decade of buybacks.

If political focus on repurchases becomes a purely temporary policy fixation, a la Joe Biden’s “CEOS should wait a year before gouging their own firms again” proposal, this bailout will be massively counterproductive, enshrining buybacks in non-emergency times as a legitimate practice. If we can’t fix a glitch as obvious as 10b-18, what can we change?