What the Creator of the Email Protocol can teach us about Politics and Religion

If you’ve never hear the term “Postel Christian”, that’s not surprising, as I’m coining it here for the first time. The term is derived from Jon Postel, the technologist who created the email protocol, and described the “robustness principle” in RFC 761, known as Postel’s Law:

Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept

The basic idea of Postel’s concept is that in certain domains it is advantageous to design systems to be forgiving (liberal) in what they accept and yet strict (conservative) in what they do. Postel’s Law allows diverse participants to function together on a network, ensuring that that the system inter-operates, despite the fact that not all participants follow the rules strictly.

Although Postel was describing the technology behind email, the same principle can be applied in other areas. In writing, for example, it is a good idea to try to follow proper spelling and punctuation, while at the same time also being forgiving of those who don’t.

Beyond Liberal vs Conservative

To extend the analogy to other domains, I consider myself neither entirely liberal or conservative. I “act” conservative in many areas of my personal life — my finances are conservative, I don’t swear, or drink. I try to respect the rules unless I feel that they are wrongheaded, yet I am freer than many self-described conservatives to associate with people of diverse backgrounds who don’t always follow the rules and I have more in common with many on the left on some social issues. So where do I fit on the Liberal-Conservative Continuum?

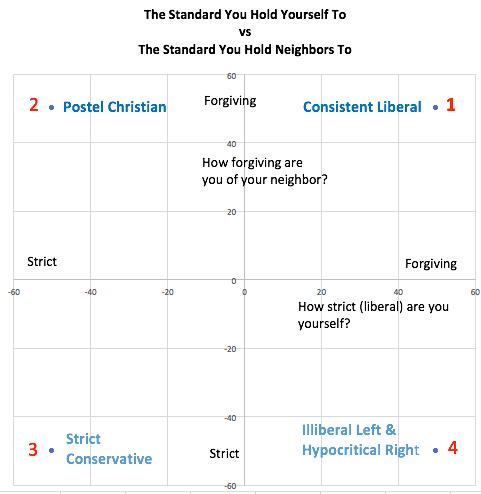

When most people think about liberalism and conservatism, they thing about about the label as applying to one’s self. What Postel’s framework does is add a second axis to distinguish between the strictness of the standard I hold myself to verses the standard with which I interact with my neighbors. Most people are familiar with The Golden Rule, which calls for a symmetry between your love of self and your love of others, but Jesus actually asked for more then symmetry, he asked for grace and did not cut off others whom did not meet the standard.

I like to think that Jesus was a “Postel Christian”. He said he had not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it, which I interpret as living according to the spirit of the law (conserving the essence of tradition), while at the same time hanging out with tax collectors and prostitutes, which would have appeared scandalously liberal to the strictly law-abiding Pharisees.

We’re in a time of change, with political realignment taking place in the Republican party. David Brooks says that Trumpism is an utter repudiation of modern conservatism. Maybe so, but maybe its also time for a broader reconsideration of the traditional Liberal and Conservative labels.

I’m an Anabaptist (Mennonite) so I’m used to not fitting within the standard Catholic/Protestant typology. Third Way.com describes some of this in more detail, but within Anabaptism there are differences in approach.

A friend of mine’s family left the Beachy Amish when he was young and then associated with conservative Mennonites. When I talked to Phil about the “Postel Christian” concept for this article, he commented that the Amish are in quadrant two. They have strict expectations for their own community, but they don’t expect others to follow them, and they are able to relate to non-believers.

He said the conservative Mennonites he knew couldn’t develop friendships with outsiders for fear that they would be corrupted. I talked this “Postel Christian” idea over with his brother Andrew and described to Andrew about how I choose to be friendly with my neighbor, even as he smokes and sits outside with a beer in his hand.1 I don’t smoke and I recognize that second-hand smoke can be damaging, but I figure in low doses it is more important to be neighborly than to protect myself. Andrew said that the people at his church would not be able to engage this way with my neighbor because they would feel an obligation to either publicly denounce the neighbor’s drinking and smoking, or shun him. For some, this response is done out of a fear that they wouldn’t be able to resist the objectionable behavior; and for others they would avoid the neighbor because they don’t want to be seen as condoning bad behavior.

Does Postel’s Law apply to all of life? Must I be forgiving of everyone?

One misunderstanding about Postel Christianity regards its scope. Say, for example, that you ran a software company. Would you as an owner or manager have to let employees do anything they want, applying a strict standard only to yourself? No, subgroups (companies, churches, civic groups) are free to hold themselves to a stricter standard.

So if I had a software company called Postel Software, I could insist that all of our HTML validates and our Python code follows the PEP 8 standard. But the key difference is that, if we are a company making a product which interoperates with web pages created by anyone on the internet, it should be designed like Google’s Chrome browser, not requiring every web page to be perfectly valid HTML. This is an accurate description of how web browsers do, in fact, work. I know of no web browser that treats html web pages strictly.

This doesn’t mean that there are not rules that can’t be broken. If I am at my local electronics shop and I see a customer attempting to steal something, I will alert to store owner. But if my neighbor is mainly harming himself, or setting a bad example, I am more forgiving.

The Benedict Option

Rod Dreher of The American Conservative has written a book called The Benedict Option, advocating that conservatives withdraw from mainstream American society to isolated communities where they can preserve Orthodox Christianity. From what I’ve read, LGBT issues are an important factor in this decision, with Rod fearing that the government is going to force Christian-affiliated schools and colleges to violate their consciences.

One of the questions I have about Dreher’s proposal is about exactly where he draws the line and why. Is he willing to interact with neighbors who may be gay, or who may think differently about LGBT issues, so long has he is able to maintain the freedom to exclude LGBT people from his churches, church-affiliated colleges, etc. If Christians are given an exception allowing them to opt out of participation in LGBT wedding ceremonies, as Skye Jethani of the Phil Vischer podcast has said, and wedding cake decorators are free to deny decorating services to LGBT couples on the theory that a cake decorating mandate violates artistic expression, would Dreher be willing to accept a mandate that required him to sell generic uncustomized cakes to anyone? Or would Dreher want to allow businesses of any kind to deny any type of service to LGBT customers?

The point I’m getting at is — is Dreher willing to coexist with his neighbors, knowing that he will come in contact with people with whom he disagrees, or does his faith require him to shun them?

If Dreher really believes that self-preservation requires him to minimize his exposure to non-believers, I can understand. I live in Lancaster County and grew up in a progressive Mennonite home without a television (although I did go to public school). My parents shielded me from some things, but they accepted that I would have to go out into a world that is at odds with the Mennonite faith and make my own choices.

Many Mennonites have developed a theology calling for separation from general society based on an interpretation of bible passages that call on believers to be “in the world but not of the world“. My church is among the more progressive of Mennonites, living a modern life (I’m a computer programmer), engaging with the world, but trying to maintain a different ethic. Critics of the type of separatism that Dreher advocates, such as Elizabeth Stoker Brunei, question how followers of the Benedict option can follow the second commandment to love their neighbor, while at the same time wanting nothing to do with them.

The Illiberal Left

A lot of the conflict in these scenarios is between quadrant three and quadrant four. Besides hypocritical conservatives, Quadrant four contains people who identify themselves as “liberal,” yet are unwilling to coexist with quadrant four conservatives.

Recently, Heather Mac Donald, author of “The War On Cops” was invited to speak to students at Claremont-McKenna College in California. One might debate whether her arguments are persuasive or wrong-headed, but the opposition among students was such that event organizers “were considering changing the venue to a building with fewer glass windows to break.” The Wall Street Journal quoted the CMC College president as saying that students had blocked people from entering the venue. Columist William McGurn attributes the conflict to the students a belief “that they should never have to hear an opinion different from their own.”

It is quadrant three and four that pose the greatest challenge to pluralism. Decreasing tolerance from quadrant four “illiberal liberals” antagonizes conservatives and drives conservatives in quadrant three like Dreher to consider separatist strategies.

Are these groups irreconcilable? I don’t know. As I interact with more people, I’m increasingly interested in looking for ways that can strengthen American pluralism, allowing Christians to learn from each other and from the broader society.2

Yes, I realize that the rules about governing alcohol and smoking are not the same in all cultures. I chose these two behaviors because they are forbidden by many of the conservatives I come into contact with.↩

I am inspired to read that René Girard became a convert to Christianity after reading literature like Cervantes and Dostoyevsky↩