Christian political engagement is about more than an issue checklist.

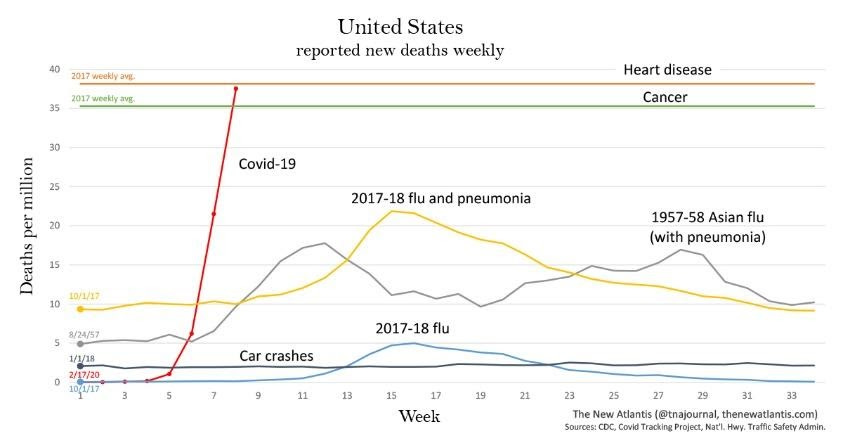

On April 15, the United States hit a horrifying milestone. It not only crossed 30,000 total COVID-19 deaths, but for the fourth consecutive day, the daily death toll was so high that COVID-19 was the single leading cause of death in the United States. This visualization of the rising death toll is simply horrifying:

At the same time, new reports have emerged demonstrating the president’s incredible reluctance to come to terms with the scale of a crisis that wasn’t just foreseeable, it was foreseen by members of his own administration. And while Trump deserves credit for limiting travel from China in late January, he not only squandered any advantage gained by that move, he actively spread misinformation about the virus throughout the month of February and into March.

Then, when he finally began to acknowledge the scale of the emergency, he went on national television and botched his own primetime address, misstating administration policies and triggering a panic from Americans in Europe who believed—based on the president’s own words—that they would be barred from coming home.

Since that time, his daily press conferences have featured a parade of presidential

- overstatements, misstatements, and outright falsehoods. He’s often fact-checked in real time by his own advisers. In the meantime, 22 million Americans have lost their jobs.

Something else happened on April 15—Albert Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the presumptive next president of the Southern Baptist Convention, and a man I respect a great deal—spoke from the midst of a ruined economy, soaring death rates, and presidential blundering and said . . . four more years. He declared not only that he’d support Donald Trump in 2020, but that he’ll almost certainly support Republican presidential candidates the rest of his life. Mohler focused on the classic culture war issues—marriage, sexuality, constitutional interpretation, and abortion. He expressed the belief that the “partisan divide had become so great” and Democrats had “swerved so far to the left” on those key issues that he can’t imagine ever voting for a Democratic president. He also claimed that Trump has been “more consistent in pro-life decisions” and consistent in the quality of his judicial nominations than “any president of the United States of any party.”

As he made clear in the video, Mohler has not always supported Trump. In 2016, he was consistent with his denomination’s clear and unequivocal statement about the importance of moral character in public officials. He has now decisively changed course.

In 1998—during Bill Clinton’s second term—the Southern Baptist Convention declared that “tolerance of serious wrong by leaders sears the conscience of the culture, spawns unrestrained immorality and lawlessness in the society, and surely results in God’s judgment” and therefore urged “all Americans to embrace and act on the conviction that character does count in public office, and to elect those officials and candidates who, although imperfect, demonstrate consistent honesty, moral purity and the highest character.”

Mohler so clearly recognized the applicability of those words that he said, “If I were to support, much less endorse Donald Trump for president, I would actually have to go back and apologize to former President Bill Clinton.” I do wonder if Mohler will apologize. He absolutely should.

Look, I know that for now I’ve lost the character argument. It’s well-established that a great number of white Evangelicals didn’t truly believe the words they wrote, endorsed, and argued in 1998 and for 18 years until the 2016 election. Oh sure, they thought they believed those words. If someone challenged their convictions with a lie detector test, they would have passed with flying colors.

(By the way, I use the term “white Evangelicals” because that’s Trump’s core political constituency. That’s the base that gave him 81 percent support in 2016. The rest of the Evangelical community leans Democratic.)

When C.S. Lewis said “courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of very virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality,” he was speaking an important truth. We may think we possess an array of virtues and beliefs, but we don’t really know who we are or what we believe until those virtues and beliefs are put to the test. There is many a man who goes to war thinking himself brave, until the bullets fly. There is many a man who thinks himself faithful to his wife, until the flirtation starts.

There were many men who thought character counted, until a commitment to character contained a real political cost. But that’s the obvious point. I’ve made it countless times before today. White Evangelicals, however, have shrugged it off. “Binary choice,” they say. “Lesser of two evils,” they say—even though those concepts appeared nowhere in the grand moral announcements of the past.

Many millions of Trump-supporting white Evangelicals no longer care about character (though a surprising number are still remarkably unaware of his flaws). That much is clear. But the story now grows darker still. As they’ve abandoned political character tests, they’re also rejecting any meaningful concern for presidential competence.

Listen to Mohler’s announcement, and you’ll hear a narrow political philosophy—one that’s limited to evaluating a party platform on a few, discrete issues. It’s nothing more than a policy checklist. He speaks of religious freedom, LGBT issues, and abortion.

Yet as the pandemic vividly illustrates (and as 9/11 also highlighted in recent years past), the job of the president extends well beyond the culture war. Indeed, there are times when a president is so bad at other material aspects of his job that he becomes a malignant force in American life, regardless of his positions on white Evangelicals’ highest political priorities.

The role of the people of God in political life is so much more difficult and challenging than merely listing a discrete subset of issues (even when those issues are important!) and supporting anyone who agrees to your list. The prophet Jeremiah exhorted the people of Israel to “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the LORD on its behalf; for in its welfare you will have welfare.”

This is a difficult, complicated task. We can’t reduce it to a list. In fact, this complexity is one reason why two key communities of churchgoing Americans are dramatically split in their political preferences. Black Christians go to church every bit as much (if not more) than white Evangelicals, yet they reject Trump every bit as much as white Evangelicals embrace him.

Are they less Christian? Or is their experience of the welfare of the national community shaped by history and experience that’s quite different from that of their white Evangelical brothers and sisters? And while that history is complex, it does clearly teach the deadly consequences of hate and the dangers of white populism.

When a president declares that there were “very fine people” in a collection of tiki-torch-toting white supremacists, shouldn’t Christians of all colors be gravely concerned? Shouldn’t they be alarmed when the CEO of the president’s campaign and his chief strategist declared just before his ascension to the president’s team that he wanted his publication (Breitbart) to be the “platform” for the racist alt-right? And when a president issues a stream of misinformation about a mortal threat to public health (with one eye on the stock market), is there not cause for accountability?

I could go on and on, but there are Christians in this country – mostly from communities who’ve suffered in the recent past at the hands of malignant government power—who look at Trump and do not see a man who’s concerned for their welfare. What is the white Evangelical obligation to listen to them? To hear their concerns?

The response can’t be the checklist. And when vulnerable Americans suffer mightily from the health and economic consequences of a global pandemic the president minimized, the response can’t be the checklist. White Evangelical leaders owe us a serious argument as to why that checklist trumps character and competence in the leader of the free world.

No one should minimize the difficulty of the job of president of the United States. It’s a fact that a number of democracies have struggled even worse than America to respond to the coronavirus (some have done much better), and economic damage will be felt worldwide. China bears immense blame for our national plight.

But President Trump was warned and warned and warned. For day after crucial day he chose to mislead Americans about one of the most significant threats to their well-being—to their “welfare”— in the modern history of the United States. He faced a key test, and he did not rise to the moment. And when he failed, he did real damage that even later course corrections could not entirely fix.

And please Christians, do not run back to arguments about “binary choice.” When I walk into the voting booth (or mail in my ballot), I will see more than two names. I’ll also have a choice to write in a name. I will not have to compromise my convictions to cast a vote for president.

If you do, however, want to revert to the language of “binary choice,” we need to examine the larger context. In January the nation faced a different kind of binary choice. It was, quite simply, “Trump or Pence.” When the president was impeached after he clearly attempted to condition vital military aid to an ally on a demand for a politically motivated investigation of a political opponent and on a demand to investigate a bizarre conspiracy theory, white Evangelicals had a decision to make.

They chose Trump.

They chose Trump when they would have certainly sought to impeach and convict a Democrat under similar facts.

In fact, for four long years, when the choice has been between Trump and even the most momentary break with the president for a single news cycle, the overwhelming majority of white Evangelicals—and their political leaders—have spoken loudly and clearly.

It’s Trump. It’s always Trump.

In the fourth year of Donald Trump’s first term, the deal white Evangelicals have struck is now increasingly clear. Their leaders will get unprecedented Oval Office access. They’ll get a few good religious liberty regulations. They’ll get good judges. Those judges will almost certainly issue rulings that protect religious liberty. They might issue rulings that marginally protect life (though the pro-life battle is fought far more in the culture and in the states than in the courts). Those will be important and good things. They are not the only things.

White Evangelicals will have also squandered any argument that character matters in politicians. That means we’ll have more politicians of low character.

White Evangelicals are squandering any argument that they seek to love their enemies. That means we’ll see more hate from America’s bully pulpit.

White Evangelicals are not only squandering any argument that competence matters, they are working hard to try to force more incompetence on their American community. Trump’s impact on the welfare of the American city is increasingly clear. It’s more division. It’s more hate. It’s more incompetence. And now that terrible combination has yielded a series of dreadful errors in the face of a deadly pandemic.

White Evangelicals, one of the most politically powerful religious movements in the entire world, should not use their power to maintain and ultimately renew the authority of one of the most malignant and incompetent politicians ever to hold national office. They shouldn’t, but they will.

One last thing …

This has been a rather grim newsletter, but authentic religious discourse requires discussing and debating hard questions, and the answers are not always easy or uplifting. I want to end not with a hymn or worship song, but rather something closer to a lament. It’s from one of my favorite artists, Sara Groves, and it speaks to the uncertainty and difficulty of life in a time of vulnerability and loss.

What is a Post-Jesus Christian?

Post-Jesus Christians are “Christians” who have decided to postpone following Jesus’s teaching until Jesus returns and ushers in 1000 years of peace.

Post-Jesus Christians hold that Jesus’s teachings do not need to be followed in our present era if they are a hindrance to obtaining the power they fear they need to help usher in the Kingdom of God.

Post-Jesus Christians (privately) hold that Jesus’s teachings are a nice thing to follow when dealing with the in-group of their fellow PJCs but may be disregarded when dealing with non-PJC neighbors.

Prophecy: What God Can Do For You

Post-Jesus Christians talk a lot about about prophecy, and unlike the Biblical Prophets, when they do, they punch down, rather than up:

You will know them by their fruit, because they only have one key message – God is going to “enlarge your tent” and “expand your influence“, he’s going to “give you great favor” and “bless you mightily”.

Later Craig Greenfield writes:

In Biblical times, there were two types of prophets.

- Firstly, there were those who feasted at the King’s table because they had been co-opted to speak well of evil leaders (1 Kings 18:19). They were always bringing these smarmy words of favor and influence and prosperity to the king. And the king lapped it up. Like a sucka.

- Secondly, there were those who were exiled to the caves, or beheaded (like John the Baptist) because they spoke out about the injustice or immorality of their leaders (1 Kings 18:4). The king didn’t like them very much. He tried to have them knee-capped.

An Inversion of Ben Franklin’s Morality

While many Post-Jesus Christians appeal to a historical “Christian Nation” , Post-Jesus Christians appear to be an inversion of founding father Ben Franklin, who in historian John Fea’s description, wanted to discard Jesus’s Divinity but retain and celebrate his ethical teachings.

Post-Jesus Christians value Jesus’s divinity, particularly his role of sacrificial lamb (for their salvation), but are eager to discard Jesus’s ethical teachings.

Interview with John Fea, author of BELIEVE ME

07:31So there was certainly the policy.07:33And then on the other hand, you had the character issues.07:39That evangelicals would sort of sell their moral authority to speak truth to the world07:50for a handful of Supreme Court justices or this or that social or cultural issue; for07:57me, the fact that this man had a history of all kinds of . . . involved in the porn industry,08:05he was crude, he disrespected women.08:10The things he said about his opponents, we could go into specifics about that.08:18I’m a believer that there needs to be some kind of moral fabric to a republic in order08:25for the republic to work.08:27Now, where you find that morality, we could debate that question; I’ve written a little08:32about that elsewhere.08:33But a moral republic needs some kind of moral leader, some person of character, and he was08:40not it.08:41And I think you could make an argument against him, not even a Christian argument; he’s just08:45not good for America.08:47But yet evangelicals were so driven by their culture war.08:52Win the culture war, get the justices we need, elect the right guy; this kind of model, “playbook”08:59I call it in the book, this playbook for winning the culture that they were willing to overlook09:05all the character flaws and that was the second thing of course that bothered me.09:10I think it bothered a lot of other evangelicals.09:12I think that character issue bothered most evangelicals, whether they voted for Trump09:17or not, but ultimately the playbook: how to win the culture wars by electing the right09:24justices, the right congressmen, and the right president was so overwhelmingly strong and09:30had been so inculcated, so indoctrinated into the way evangelicals today think about politics,09:38that I should have seen it coming.09:42I should have seen this–if you look at the past 15 years, this was all building up to09:47this point.09:48Now, I think, I tend to think of this as kind of a last gasp of the old Christian Right;09:56I think that most of the people who voted for Trump came of age during the late ’70s10:03and ’80s when people like Jerry Falwell and the Christian Right were articulating this10:08playbook for how to win the culture for the first time.10:12I think the average Trump voter is 57 years old.10:16So I do have hope, especially as I look at young people in Christian colleges, like Messiah10:21College where I teach, who are much more interested in different kinds of questions related to10:27justice and social ills and those kinds of things in terms of how they exercise their faith.10:32But I think, I hope this is, I think I see this as a last gasp–I think in the book I10:39call it–I occasionally teach a course on the Civil War.10:44Some of your viewers might remember the last great engagement of the Battle of Gettysburg:10:53Picket’s Charge where the Confederate, Confederacy made one last charge before they were–and11:00almost were successful–before they were beat back once and for all.11:04Those who know their Civil War history know the war went downhill from that point.11:10I hope that’s what happened, that’s what’s gonna happen, that’s what we’re seeing here.11:16So, as I look back, I looked at the last 50 years, I saw all of these grievances that11:26evangelicals believed were happening, whether they be sexual politics: abortion; the ERA, the11:36Women’s Rights movement.11:38Evangelicalism has always been a patriarchal culture.11:45I think there’s a reaction to that.11:46I think there was a reaction to integration, racial integration, desegregation.11:54I think there were prayer in public schools, Bible taking out of the public schools, prayer11:59removed from public schools.12:00I think there’s this perfect storm that emerges in the ’60s and ’70s that prompts people likeJerry Falwell and others to establish again this kind of political playbook to win theculture back.12:14And Trump proved that, just how powerful that playbook really is and continue–was, and12:22continues to be, even to the point that someone like Donald Trump could win.12:28Again, I’m writing primarily to evangelicals in this book.12:33I think there will be a secondary audience of American religious historians, people who12:38are interested in American religion who want to take a peek into what evangelicals are12:43talking about.12:44I think there’s some good history in the book, though, too.12:46One of the things I try to unpack is show how there’s always been a dark side to American12:52evangelicalism.12:55We can talk about the way in which evangelicals have been on the front lines of anti-slavery,social justice movements, international poverty relief, all of these kinds of things.And we need to celebrate that I think; I’m not one of these people, who–I am an evangelical,so I rejoice that evangelicals are doing these things.But there’s also a dark side.Even as someone like Lyman Beecher, who I write about in the third chapter, even ashe is fighting slavery, he’s also one of the leading nativists.He doesn’t want catholics coming in and undermining his protestant nation.So this story goes back a long way and I think what Trump does, is he appeals to the worstside of evangelicalism in its 2, 300-year history.Every time evangelicals are not representing the true virtues of their faith, where they13:58fail, I think Trump seizes on that history.14:04This is a history that defended the institution of slavery.14:07This is a history that had such certainty about what is true in the fundamentalist movement.14:16This is a movement that prevented, didn’t want certain kinds of immigrants coming into14:20the country.14:21There’s a long history of this.14:23I’d like my fellow evangelicals to at least be exposed to that history.14:29I think when ordinary evangelicals, lay men and women, think about evangelical history14:35they celebrate this providential idea.14:38“God is with us!14:40God is doing great things through people.”14:42And I think that’s important.14:44I think God does obviously work in this world and uses people in this world.14:49But also the reality of human sin: evangelicals are not immune.14:55Obviously!14:56If anyone knows better, it’s an evangelical who believes in this conversion experience,15:03one’s saved from the consequences of sin, becoming born again or becoming–accepting15:08Jesus, or whatever that looks like.15:12So, I want them to see there is a darker side to the history that Trump is tapping into.15:21Am I going to convince the 81% that they made a wrong decision?15:28Most I probably will not, but I do believe there are some fence-sitters out there, people15:32who maybe held their nose and voted for Trump.15:39Maybe they need to think through exactly, they may be open to thinking through a little15:43bit more, in terms of what this man represents and what the policy decisions he is putting15:49forth represent.15:52And hopefully it will force evangelicals–maybe “force” is too strong a word, but it might15:55encourage evangelicals to think more deeply about political engagement.16:04And when a politician comes along and says, “Let’s make America great again,” he’s ultimately–or16:11she, in this case he–is ultimately making a historical statement.16:17So I think evangelicals have to be careful.16:19When was America great?16:22Let’s go back and think about that.16:24What does Trump mean when he says, “Make America great again?”16:28And before you start using these evangelical catch-phrases like “reclaim” and “restore”16:34and “let’s get back to” and “let’s bring back the way it used to be,” we need to think more16:44deeply about what, exactly what it was like back then, how it used to be.16:49So I think even if the book forces evangelicals to kind of rethink even their phraseology16:55and how they, what they say when they enter the public sphere, public square, I think17:00that will be a contribution in some ways.17:02I’ll be happy if that happens.17:06So I think race plays an important role in this book.17:11I think that’s a contribution here.17:13There’s a lot of reasons why evangelicals voted for Trump.17:17Sexual politics I think is a big one.17:19I think race is also an issue.17:22There is a certain degree of, still a certain degree of fear among white evangelicals that,17:30not only African Americans, but Hispanics; America’s becoming less white, there’s been17:36a lot of good sociology written about this lately about the “end of white America.”17:41So I think this is, the white evangelicals who voted for Donald Trump, the 81% of white17:48evangelicals, are responding to these changes with a sense of fear, with a sense of nostalgia17:56for a white world in which they held power.17:59So I think this is part of the story, part of the appeal of Donald Trump.18:06Let’s try to, when they say, “Let’s make America great again,” you talk to most African Americans,18:13the best time to live in America is today.18:16They don’t want to go back.18:18And I’ve had some great conversations over the years with African American evangelicals18:22and worked with them on things and I talk a little bit about that in one of the chapters18:26of the book about this idea that we are somehow a Christian nation that we have to get back to.18:35No African American wants to get back to when we were supposedly a “Christian nation.”18:40So I think this appeal–and again, you see it in the history.18:44Whenever there is some kind of significant cultural change, whether it be religion, race;18:51I mean, I’m half Italian.18:53When my Italian family came over, they were of a “different race.”18:58They were southern Europeans.19:00They weren’t WASPs.19:01So this same kind of racial rhetoric, as well as the anti-catholic rhetoric.19:07Whenever there’s a cultural demographic change in society, largely through immigration, or19:14some kind of slave rebellion where the slaves are threatening to overthrow the racial hierarchy19:19of the South, sadly, evangelicals are always at the front of that resistance.19:28Mostly white, middle class evangelicals.19:30I think that’s what you’re seeing again now.19:32Our culture is changing.19:34We’re becoming less white, we’re becoming more religiously diverse.19:38I think the 1965 Immigration Act which allowed non-Western men and women into this country.19:45They brought their religions with them, they brought their culture with them.19:50And I think Donald Trump stepped in and said, in a very conservative, populist way–which19:55we’ve seen throughout American history, maybe most recently Pat Buchanan, but there were19:59others in the 20th Century–and said, “We are going to make you happy again.20:07We’re gonna give you the kind of world that you once knew as a kid.20:11We’re gonna make America great again.”20:14And I think that is very much tied into these racial, cultural, ethnic changes.20:20For a long time, evangelicals have been, if not leading, very much at the forefront of20:28racism in America.20:31I would argue historically–really more as an evangelical, I would argue–it’s a failure20:40of their, it’s a failure of faith.20:44I think evangelicals have these resources, all Christians have these resources: the dignity20:49of all human beings.20:53I think it’s most important, but also evangelicalism specifically…21:00I remember hearing Mark Galli, the editor of Christianity Today, talking about all these21:06Christian scholars that appeal to the Imago Dei which is we’ve been created in the image21:11of God, and thus everybody has dignity, everybody has worth: racism is not an option as a result21:19of that, if everybody has dignity.21:21And there were people in the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th Centuries who were making these arguments,21:27so it’s not as if I’m sort of taking my 21st Century view on this and superimposing it21:33on the past.21:34There are others who were more consistent on this.21:36But Galli said for evangelicals, it even goes deeper than just the Imago Dei, or it’s more21:42thorough than that, in the sense that, if we believe Jesus died on the cross for our21:49sins, redemption, all human beings are worthy of redemption in God’s eyes regardless of21:56gender, race, class, and so forth.21:59So it moves even beyond just the creation to the redemption.22:04So I think evangelicals have an amazing set of resources in their faith to be able to22:10overcome these racial problems and, for a variety of reasons, they’ve failed to do it22:18because I think they’re overcome by fear in many ways.22:23They’re overcome by–and this deeply rooted idea that somehow we are an exceptional nation,22:30God has blessed us above other nations, that we are a new Israel.22:35In some ways evangelicals still believe they’re in this kind of contractual relationship with22:41God–Americans are–Evangelicals believe if we don’t keep a pure Christian nation we’re22:50gonna lose God’s favor in some ways.22:56So I think all of those really bad historical assumptions and theological assumptions–fear,23:06I don’t think–I love the Marilyn Robinson quote: “fear is not a Christian habit of mind.”23:12So there’s these kinds of psychological, theological errors, historical errors that get in the23:22way of us living out our faith with a sense of hope, with a sense of equality, with a23:29sense of what Martin Luther King called the “beloved community.”23:34I think there’s gonna be a lot of people, and there have been a lot of people who after23:37the election of Donald Trump–you know, I was close to this as well; I would even argue23:41at one point that I was there maybe for a few days.23:44I tended to work out my, what’s the word, angst or whatever about this kind of publicly,23:51so, if you follow the paper trail: two days after the election I’m saying, “Here’s what I’m still23:59thankful for!”24:00So, I’m still–I just gave a talk last week to the board of trustees of a Christian college,24:07and they gave me the assignment.24:09The assignment was this: What positive role has evangelicalism played in American history?24:19You know, that’s a tough question for a historian.24:23Especially after the previous question I answered about the dark side of evangelicalism.24:29That’s a tough question because we don’t tend to speak in moral categories, “It’s good” or24:34“bad;” no, this is what happened, and you guys parse it out.24:38But, I respect the people who have decided to leave evangelicalism.24:43A lot of my friends have, and people who–or at least, rejected the label, let’s put it24:48that way–some of my unofficial mentors have said it’s not useful anymore; let’s use the24:57term “evangelical” or “evangelicalism” to describe a historical movement, phenomenon,25:04but it’s become so politicized.25:06So you also have the examples of Princeton’s Evangelical Fellowship, their student group;25:14they took “Evangelical” out of their name.25:17You see a lot of big megachurches–and I think this happened before Trump, but they’re removing25:22the term “evangelical” because it has such political connotations.25:27I respect that; for me . . . and it’s really through a lot of discussions with my editor David Bratt25:35on this; he convinced me that I’m actually in the process of defending the term in this25:42book.25:43I’m not willing to let it go to the politician, to the court evangelicals, or the 81%.25:54I think there’s something about “evangelical,” the word, the good news, the gospel, the authority26:01of the Scriptures, the cross, that’s worth defending, and worth saving from the way it’s26:11been so politicized.26:13So I think when you read this book, I think you’ll still see me kind of struggling with26:17this a little bit because I’ve always been a very uneasy evangelical since I converted,26:24I would say “got saved” at age 16.26:28I’ve always been uneasy because I was formed in another religious tradition that also had26:32a profound effect on my moral formation and upbringing.26:36But,26:39while I remain uneasy with evangelicalism, I’m not willing to go all the way and say26:48I’m not going to identify with that term.26:50I think, I often find myself, since the election–as much as I’m a critic of what the 81% did by27:00voting for Trump, I get, the hairs on my arm raise, too, when I hear secular liberals27:10trashing evangelicals.27:13I want to say, “No!”27:15I get angry, too, at the kind of assault on evangelicals.27:19A perfect example of this is after the death of Billy Graham.27:24My natural instinct was to say this man lived a–he had flaws, we all have flaws; he could27:31have maybe done more in certain areas, but this man lived an honorable, God-fearing life as27:37I understood it.27:38Again, he had his slip-ups.27:39I actually write about some of his slip-ups in the book.27:43But I just thought the sort of secular liberal–whatever you want to call it–the anti-evangelical27:50assault on Billy Graham in some popular pieces was just way over the top.27:56And they were making criticisms that no right-minded historian would make.28:02Talk about the right and wrong sides of history and Graham was on the wrong side, and these28:07were people, a lot of them actually were former evangelicals with axes to grind, I’ll say28:13that publicly I think, you know who you are!28:18But, what fascinates me is someone needs to do a study of how the election of Donald Trump28:30influenced obituaries and other popular op-eds and stuff of Billy Graham.28:38Because some people are just connecting Graham to the court evangelicals and there’s some28:41truth to that, but the venom in a lot of pieces on Graham really got under my skin and that’s28:52maybe saying more about me than them, I don’t know, but that’s an example of where I will. . .29:00people are going to think I’m enemy number one after, public enemy number one after they read this29:05book, but I just want to affirm that I remain an evangelical.29:10I still believe in those things that evangelicals believe in and I’m always going to be a critic, too.29:21Insider/outsider kind of thing.29:24For those who left evangelicalism, or at least don’t want to associate with the term, I respect29:28that; I’m not going to try to write another book to win you back, and I think that’s a29:35fair position to take.29:37I’m just not going to take, I’m not one to take that position.