“As a former CIA officer, I know this playbook,” Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Va.) said in a tweet. Before her election to Congress last year, she worked at the agency on issues including terrorism and nuclear proliferation.

One U.S. intelligence official even ventured into downtown Washington on Monday evening, as if taking measure of the street-level mood in a foreign country.

“Things escalated quickly,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing the sensitive nature of his job. He emphasized that he went as a concerned citizen, not in any official capacity. After seeing tear gas canisters underfoot, he said, he “knew it was time to go” and departed.

Former intelligence officials said

- the unrest and the administration’s militaristic response are among many measures of decay they would flag if writing assessments about the United States for another country’s intelligence service.

- They cited the country’s struggle to contain the novel coronavirus,

- the president’s attempt to pressure Ukraine for political favors, his

- attacks on the news media and the

- increasingly polarized political climate as other signs of dysfunction.

Trump supporters have defended his handling of the unrest, and his trip across Lafayette Square as a display of the strength needed to restore order in dozens of cities where protests have led to looting, fires and violence.

Former Wisconsin governor Scott Walker (R) said it was “hard to imagine” any other president “having the guts to walk out of the White House like this.”

But there were also indications that senior members of the administration were uncomfortable with the president’s outing and eager to minimize their role in it.

A senior Pentagon official said Tuesday that neither Esper nor Milley knew when they set out to accompany Trump that police were about to charge through seemingly peaceful protesters or that they would play supporting roles in a photo op.

Even away from the cameras, Trump has assiduously cultivated the aura of a strongman. Earlier Monday, he had chided governors as “weak” for failing to employ adequate force in the face of mounting protests.

“If you don’t dominate, you’re wasting your time,” Trump said. He offered no words on how to ease tensions in crowds that have massed largely in anger over the death of George Floyd, an African American man who was killed while being pinned to the ground, a knee against his neck, by police in Minneapolis.

Brett McGurk, a former top U.S. envoy to the Middle East who spent two years in the Trump administration, said the president’s words — recorded by participants and shared with news organizations — would only embolden the world’s autocrats and undermine U.S. authority.

“The imagery of a head of state in a call with other governing officials saying, ‘Dominate the streets, dominate the battlespace’ — these are iconic images that will define America for some time,” said McGurk, who led U.S. diplomatic efforts to counter the Islamic State terrorist group. “It makes it much more difficult for us to distinguish ourselves from other countries we are trying to contest” or influence, he said.

In recent years, U.S. officials have urged restraint or denounced crackdowns against protesters or vulnerable groups in Russia, Iran, Turkey, Malaysia, Syria and other countries.

Even this week, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo lectured China about its efforts to prevent citizens of Hong Kong from holding a vigil to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests.

“If there is any doubt about Beijing’s intent, it is to deny Hong Kongers a voice and a choice,” Pompeo said in a statement that was met with derision on Twitter because it coincided with crackdowns urged by Trump in the United States.

The seeming hypocrisy in the U.S. position has not been lost on foreign targets of American pressure or criticism.

Ramzan Kadyrov, a Chechen leader who has faced U.S. sanctions for alleged human rights abuses, said Tuesday that he was “watching with horror the situation in the United States, where the authorities are maliciously violating ordinary citizens’ rights,” according to reports from Moscow.

The United States is a country to be pitied

No amount of patriotism or pride can change the appalling facts. The pandemic is acting as a stress test for societies around the world, and ours is in danger of failing.

I’m used to thinking of a nation such as South Korea as a kind of junior partner, a beneficiary of American expertise and aid. Yet the U.S. death toll from covid-19 exceeds 85,000 while South Korea’s fatalities total 260. That is not a typo. How could a nation with barely half our per capita income have done so much better? Washington has been Seoul’s patron and teacher for more than six decades, yet somehow we apparently have unlearned much of what we taught.

Much closer to home, Trump’s boasting about how his border wall is supposedly helping protect Americans against the virus is a joke. Mexico’s reported death rate from covid-19 is a small fraction of ours (though the numbers may be higher than the official count). In the border town of Nogales, Mexican authorities are using disinfectant spray to sanitize visitors arriving from Arizona.

How could it be that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which I always thought of as the premier public health agency in the world, so completely botched the development of a test for the novel coronavirus? We have by far the biggest economy in the world, and we believe we have the most advanced science. Yet for the first months of the pandemic, as the coronavirus silently spread, we were essentially blind. By the time we had eyes on the enemy, it was too late.

We have managed to slow the spread of the virus, but I worry we lack the social cohesion to stay the course. On Wednesday, the Wisconsin Supreme Court invalidated Gov. Tony Evers’s (D) extension of his stay-at-home order. By evening, bars in some Wisconsin cities were packed — no social distancing, no masks. In Milwaukee and several other jurisdictions, however, orders by local officials kept the bars closed. What are the Wisconsin cities that remain closed supposed to do? Set up roadblocks to keep outsiders away?

The Florida Keys have done just that: Since March 27, checkpoints have been in place to keep visitors from entering the island chain — which has seen just 95 cases of covid-19 and only three deaths. The America I know, or thought I knew, is one of restlessness, free movement, open roads. Until there is a vaccine, post-covid America may be very different.

Thanks to Trump, we have no coherent national plan to survive the pandemic. But also thanks to the federal government — and I include Congress as well as the president — we lack the kind of sturdy economic safety net that protects unemployed workers and shut-down business owners in some of the hardest-hit European countries — nations that once looked up to the United States as a model. In the Netherlands, for example, the government is granting employers up to 90 percent of their payroll costs so they can keep paying their workers rather than resort to furloughs or layoffs. That kind of continuity ought to speed recovery when reopening becomes safe.

The European Union is working with the World Health Organization and other wealthy nations such as Japan and Saudi Arabia in a crash program to develop a covid-19 vaccine, with initial funding of $8 billion. The United States has decided to go it alone with its own vaccine program, “Operation Warp Speed.” In the past, one might have bet on U.S. ingenuity and drive to win the race. But given our failure in testing, would you still make that bet now? And why is there a race at all, rather than a U.S.-led global effort?

The covid-19 pandemic has exposed the depth of America’s fall from greatness. Ridding ourselves of Trump and his cronies in November will be just the beginning of our work to restore it.

The Arrival Of The ‘Unavoidable Pension Crisis’

I wrote an article in 2017 discussing the “Unavoidable Pension Crisis.” At that time, most did not understand the risk.

Since then, the situation has continued to worsen.

COVID-19 pandemic has likely triggered a rolling pension collapse over the next couple of years.

This idea was discussed in more depth with members of my private investing community,Real Investment Advice PRO.

In 2017, I wrote an article discussing the “Unavoidable Pension Crisis.” At that time, most did not understand the risk. However, two years later, the “Unavoidable Pension Crisis” has arrived.

To understand we are today, we need a quick review.

“Currently, many pension funds, like the one in Houston, are scrambling to marginally lower return rates, issue debt, raise taxes, or increase contribution limits. The hope is to fill the gaping holes of underfunded liabilities in existing plans. Such measures, combined with an ongoing bull market, and increased participant contributions, will hopefully begin a healing process.

Such is not likely to be the case.

This problems are not something born of the last ‘financial crisis,’ but rather the culmination of 20-plus years of financial mismanagement.

An April 2016, Moody’s analysis pegged the total 75-year unfunded liability for all state and local pension plans at $3.5 trillion. That’s the amount not covered by fund assets, future contributions, and investment returns ranging from 3.7% to 4.1%. Another calculation from the American Enterprise Institute comes up with $5.2 trillion, presuming that long-term bond yields an average 2.6%.

With employee contribution requirements extremely low, the need to stretch for higher rates of return have put pensions in a precarious position. The underfunded status of pensions continues to increase.”

The Crisis Is Here

Since then, the situation has continued to worsen as noted by Aaron Brown in 2018:

“Today the hard stop is five to 10 years away, within the career plans of current officials. In the next decade, and probably within five years, some large will face insolvency,

We are already there. Here was the key sentence in Brown’s commentary:

“The next phase of public pension reform will likely be touched off by a stock market decline. Such creates the real possibility of at least one state fund running out of cash within a couple of years. The math says that tax increases and spending cuts cannot do much.”

Brown was right, and the COVID-19 pandemic has likely triggered a rolling pension collapse over the next couple of years. Via the NYT:

“Now the coronavirus pandemic have it ticking faster.

Already chronically underfunded, pension programs have taken huge hits to their investment portfolios over the past month as the markets collapsed. The outbreak has also triggered widespread job losses and business closures that threaten to wipe out state and local tax revenues.

That one-two punch has staggered these funds, most of which are required by law to keep sending checks every month to about 11 million Americans.”

Over Promise Under Deliver

Here is the real problem:

“Moody’s investor’s service estimated that state and local pension funds had lost $1 trillion in the market sell-off that began in February. The exact damage is hard to determine, though, because pension funds do not issue quarterly reports.”

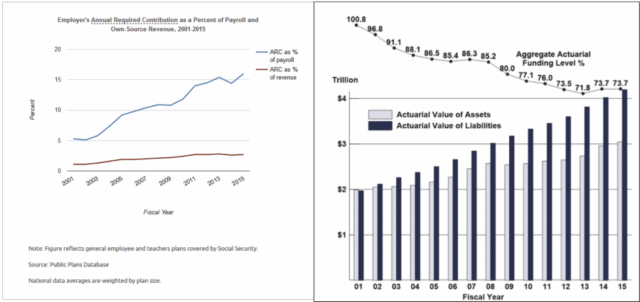

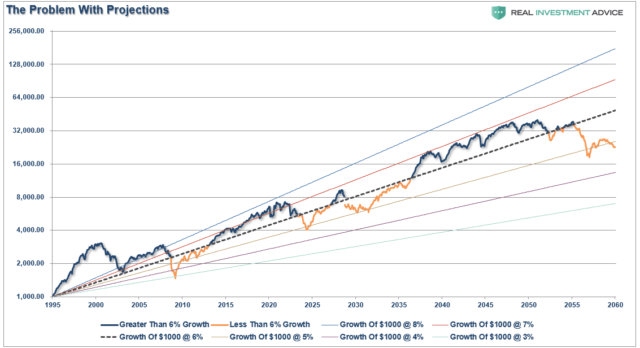

At the end of the year, we will find out the true extent of the damage. However, this is not, and has not been, a real plan to fix the underfunded problem. “Hope” for higher rates of sustained returns continues to be the only palatable option. However, targeted returns have continuously fallen short of the projected goals.

To wit:

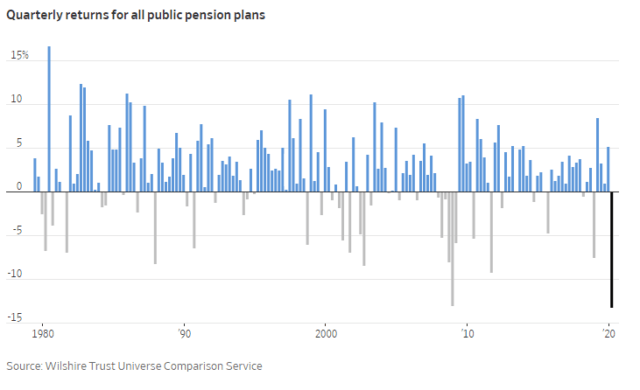

“Over the past decade, public pensions had ramped up stockholdings and other risky investments to meet aggressive return targets that average around 7%.

For the 20 years ended March 31, public pension-plan returns have fallen short of that target, however, returning a median 5.2% according to Wilshire TUCS.”

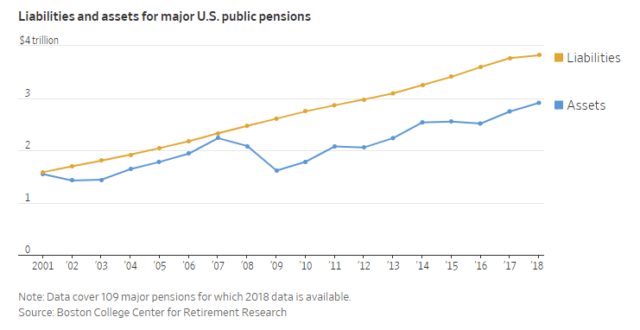

While State and Local governments all want to ignore the problem, it is isn’t going away. There is a simple reason why pensions are in such rough shape: The amount owed to retirees is accelerating faster than assets on hand to pay those future obligations. Liabilities of major U.S. public pensions are up 64% since 2007, while assets are up 30%, according to the most recent data from Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research.

More importantly, there is nothing that can, or will, change the two pre-existing problems which have plagued the economic shutdown is exacerbating pensions.

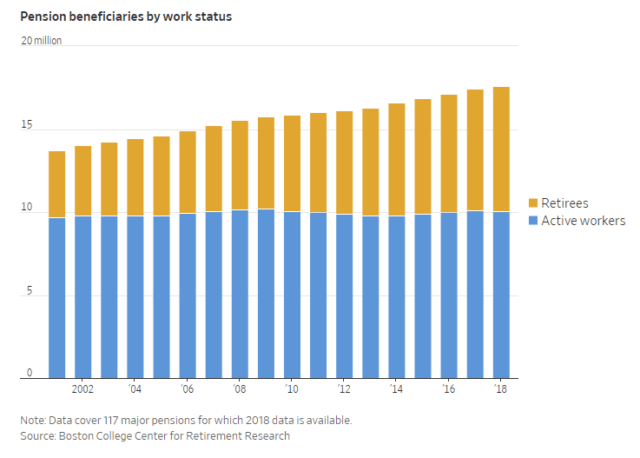

Problem #1: Demographics

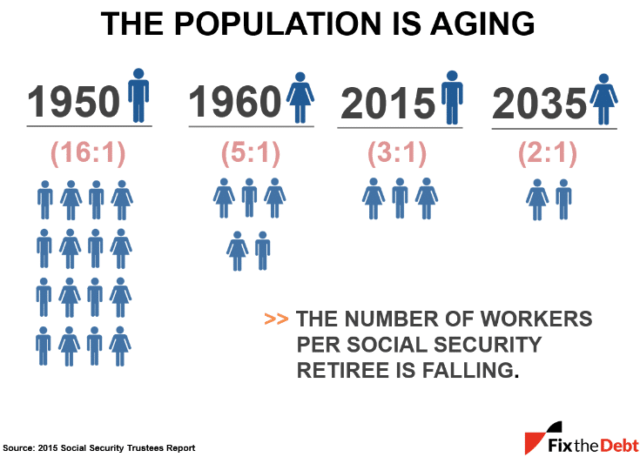

With pension funds already wrestling with largely underfunded liabilities, demographics are another problem as baby boomers age. The number of pensioners has jumped due to longer lifespans and a wave of retirees over the past decade, while the number of active workers remained relatively stable.

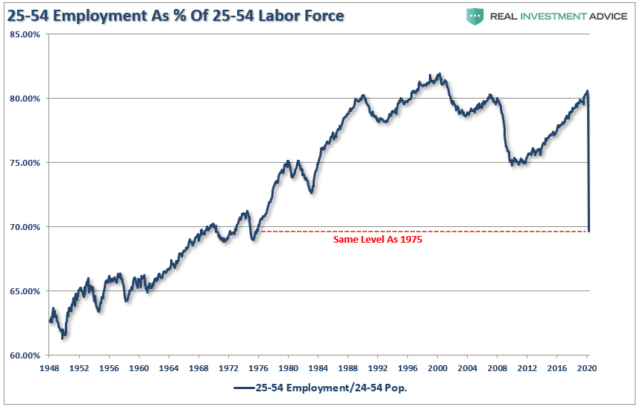

The problem compounds as the labor-force participation for the prime-age working group of 25-54 years of age declines due to the economic shutdown.

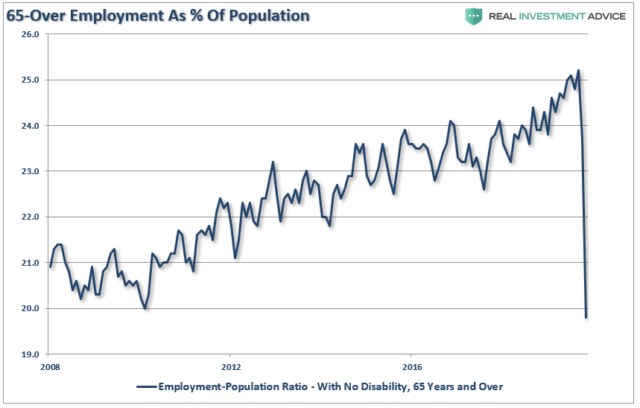

At the same time, companies are forcing the over-65 participants into retirement. These individuals are immediately able to start taking pension distributions.

A Fertility Problem

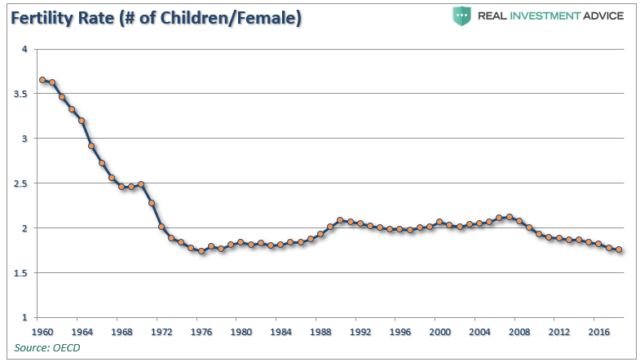

One of the primary problems continues to be the decline in the ratio of workers per retiree as retirees are living longer (increasing the relative number of retirees), and lower birth rates (corresponding number of workers.) Such is due to two demographic factors:

- An increased life expectancy coupled with a fixed retirement age; and,

- A decrease in the fertility rate.

In 1950, there were 16-workers per social security retiree. By 2015, the support ratio dropped to 3:1, and by 2035 it is projected to just 2:1.

As discussed previously, the problem is that while the “baby boom” generation may be heading towards retirement years, there was little indication they were financially prepared to retire. To wit:

“As part of its 2019 Savings Survey, First National Bank of Omaha examined Americans’ habits, behaviors, and priorities when it comes to saving, monthly spending, and retirement planning. The findings showed that nearly 80% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck.

Many have now been “asked to retire,” which means they cannot collect unemployment benefits. They are also permanently removed from the labor force.

Such is particularly problematic for pension funds because this will lead to an immediate demand for payouts at a time when pension fund assets decline. Unfortunately, the ultimate burden will fall on those next in line.

Problem #2: Markets Don’t Compound

The biggest problem is the computations performed by actuaries. The assumptions regarding current and future demographics, life expectancy, investment returns, levels of contributions or taxation, and payouts to beneficiaries, among other variables, consistently turn out wrong.

Using faulty assumptions is the linchpin to the inability to meet future obligations. By over-estimating returns, it has artificially inflated future pension values. However, high expected returns are required to reduce the required contributions to the pension plans.

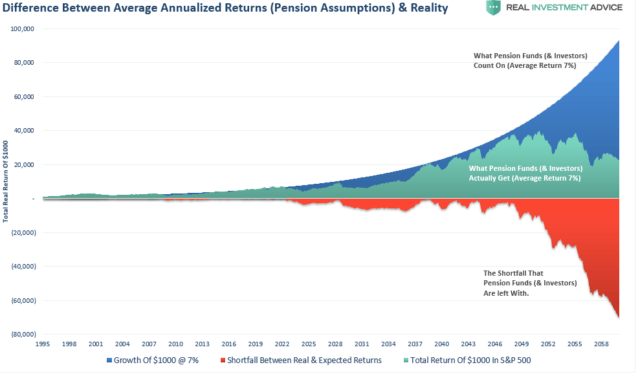

There is a significant difference between actual and compounded (7% average annual rate) returns. The market does NOT return an AVERAGE rate each year, and one negative return compounds the future shortfall. (Forward projections are a function of expected return values due to rising deficits, valuations, and demographics.)

With pensions still having annual investment return assumptions ranging between 6–7%, 2020 will likely be another year of underperformance.

As noted, pensions do not have much choice but to hope for high returns. If expected returns decline by 1–2 percentage points, the required contributions increase dramatically. For each point of reduction in the assumed return rate, pensions require a roughly 10% increase in contributions.

For many plan participants, particularly unionized workers, increases in contributions are difficult to obtain. Pension managers must maintain better-than-market return assumptions that requires them to take on more risk.

Guiding Down

But therein lies the problem.

The chart below is the S&P 500 TOTAL return from 1995 to present. Projected returns use variable rates of market returns with cycling bull and bear markets, out to 2060. I have also added projections of 8%, 7%, 6%, 5%, and 4% average rates of return from 1995 out to 2060. (I have made some estimates for slightly lower forward returns due to demographic issues.)

Given real-world return assumptions, pension funds SHOULD lower their return estimates to roughly 3-4% to potentially meet future obligations and maintain some solvency.

Again, pension funds won’t, and really can’t, make such reforms because “plan participants” won’t let them. Why? Because:

- It would require a 30-40% increase in contributions by plan participants they simply can not afford.

- Given many plan participants will retire LONG before 2060 there simply isn’t enough time to solve the issues, and;

- The bear market is already further crippling plan’s abilities to meet future obligations without massive reforms immediately.

Government Bailouts

Such is why municipalities across the country have been lobbying the Democratically controlled Congress to pass another funding bill to provide financial relief. The bill, passed by House Democrats, specifically included the following:

The cornerstone of the 1,800-page bill is $875 billion for state and local governments.

Unfortunately, $875 billion is a drop in the bucket.

The real crisis comes when there is a ‘run on pensions.’ With a large number of pensioners already eligible for their pension, the next decline in the markets will likely spur the ‘fear’ that benefits will be lost entirely.

The combined run on the system, which is grossly underfunded, at a time when asset prices are declining will cause a debacle of mass proportions. It will require a massive government bailout to resolve it.”

This is why the Fed is terrified of a market downturn. The pension crisis IS the “weapon of mass destruction” to the financial system, and it has started ticking.

Pension plans in the United States have a guarantee by a quasi-government agency called the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (OTC:PBGC), the reality is the PBGC is nearly bust from taking over plans following the financial crisis. The PBGC will run out of money in 2025. Moreover, its balance sheet is trivial compared to the multi-trillion dollar pension problem.

We Are Out Of Time

Currently, 75.4 million Baby Boomers in America—about 26% of the U.S. population—have reached or will reach retirement age between 2011 and 2030. Many of them are public-sector employees. In a 2015 study of public-sector organizations, nearly 50% of the responding organizations stated they could lose 20% or more of their employees to retirement within the next five years.

Local governments are particularly vulnerable: a full 37% of local-government employees are at least 50-years of age in 2015.

It is now 5-years later, and the problems are worse than before.

It is no surprise that public pension funds are completely overwhelmed, but they still do not realize that markets do not compound at an annual return of 7% annually. Such has led to the continued degradation of funding levels as liabilities continue to pile up

If the numbers above are right, the unfunded obligations of approximately $5-$6 trillion, depending on the estimates, would have to be set aside today such that the principal and interest would cover the program’s shortfall between tax revenues and payouts over the next 75 years.

That isn’t going to happen.

The “unavoidable pension crisis” has arrived, and the consequences will devastate many Americans, depending on their retirement pensions.

“Demography, however, is destiny for entitlements, so arithmetic will do the meddling.” – George Will

Whatever amount you are saving for retirement is probably not enough.

Betsy DeVos openly admits she’s using the pandemic to impose her private school choice agenda

“Yes, absolutely,” DeVos replied when asked if she was trying to “utilize” the crisis to help “faith-based schools”

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos admitted that she was trying to use the ongoing coronavirus crisis to push through her private school choice agenda during a Tuesday radio interview. DeVos made the comments during an interview with Cardinal Timothy Dolan, the archbishop of New York, on his Sirius XM show. The interview was first flagged by the nonprofit education news outlet Chalkbeat.

Dolan asked the secretary whether she was trying to “utilize this particular crisis to ensure that justice is finally done to our kids and the parents who choose to send them to faith-based schools.”

“Am I correct in understanding what your agenda is?” he asked.

“Yes, absolutely,” DeVos replied. “For more than three decades, that has been something that I’ve been passionate about. This whole pandemic has brought into clear focus that everyone has been impacted, and we shouldn’t be thinking about students that are in public schools versus private schools.”

Department of Education spokeswoman Angela Morabito said in a statement to Chalkbeat that DeVos “is helping Catholic schools just as she is helping all schools; this does not mean she is favoring any one type of school over another.”

“There is no question that this crisis has impacted all students — no matter what kind of school they’re enrolled in,” she added.

DeVos’ comments came as she defended her decision to redirect coronavirus relief funds away from public schools with high numbers of impoverished students to private schools which tend to serve wealthy students. Congress allocated about $13.5 billion to help schools, most of which was intended to go to schools based on a formula that determines how many poor children they serve.

The formula has long allocated some of the funding for poor children who attend private schools, The Washington Post reported. But DeVos said states should calculate how many total students private schools serve rather than just the number of poor students. As a result, millions in aid will be redirected away from schools with high poverty rates to private schools which may not have many poor students.

The move drew criticism from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

“My sense was that the money should have been distributed in the same way we distribute Title I money,” Sen. Lamar Alexander, R-Tenn., the chairman of the Senate Education Committee who is typically a DeVos ally, told reporters Wednesday. “I think that’s what most of Congress was expecting.”

Democrats also decried the decision.

“[The guidance] seeks to repurpose hundreds-of-millions of taxpayer dollars intended for public school students to provide services for private school students, in contravention of both the plain reading of the statute and the intent of Congress,” House Education Chairman Bobby Scott, D-Va., House Education Appropriations Subcommittee Chairwoman Rosa DeLaura, D-Ct., and Senate Education ranking member Patty Murray, D-Wash., said in a letter to DeVos on Tuesday.

“Given that the guidance contradicts the clear requirements of the CARES Act, it will cause confusion among states and local education agencies that will be uncertain of how to comply with both the department’s guidance and the plain language of the CARES Act,” the lawmakers urged, asking her to “immediately revise” the guidance.

But DeVos defended the decision Thursday to reporters.

“It’s our interpretation that [the funding] is meant literally for all students, and that includes students no matter where they’re learning,” she said.

The Democrats’ warning has proven right, however, as states are already dealing with confusion sparked by the policy.

The Education Law Center said DeVos’ policy was a “patent misreading” of the federal law and could redirect $800,000 in aid from Newark Public Schools in New Jersey to private school students. Tennessee’s education chief said she plans to follow DeVos’ guidance, but other school leaders argue that it is not legally binding and should be ignored.

Indiana’s schools chief Jennifer McCormick said that the state would ignore the guidance after consulting with the state’s attorney general.

“I will not play political agenda games with relief funds,” she said.

Scott told NPR that “there is rightfully pushback” on the decision.

“The actions of the Department of Education have left states and districts stuck between compliance with the law,” he said, “and adhering to ideologically motivated guidance.”