Protecting Democracy from Corporate Money While Allowing Transparent Corporate Speech

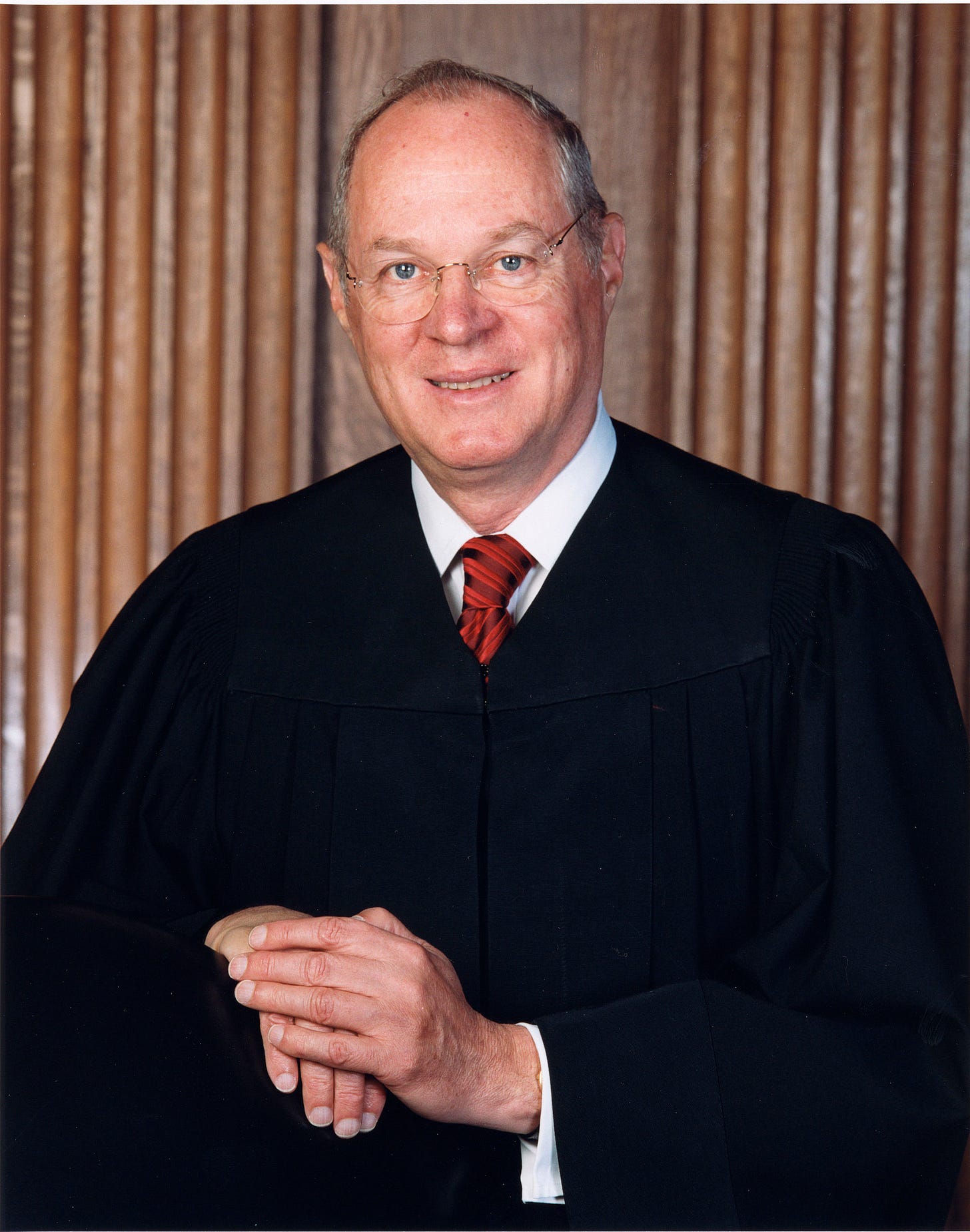

A Proposal That Honors Justice Anthony Kennedy’s Vision of Corporate “Information”

Throughout American history, rights have typically expanded rather than contracted. However, the unique challenges facing American democracy today may warrant rethinking certain rights afforded to large corporations. Mitt Romney famously remarked that Corporations are people

, and while that concept has become embedded in U.S. law, it has arguably gone too far. Expansions in corporate “personhood” and “speech” (i.e., political spending) have disproportionately elevated corporate influence in politics, often at the expense of the American electorate.

The rise in corporate political spending has suppressed the voice of average voters and contributed to their sense of disillusionment. In 2014, Studies by political scientists Martin Gilens1 and Benjamin I. Page 2 revealed the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.

This imbalance distorts democratic governance, where elected officials increasingly prioritize the interests of the wealthy and corporations over those of the median voter.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling defended corporate political expenditures as “speech,” with Justice Anthony Kennedy opposing restrictions on corporate “speech,” saying Corporations have lots of knowledge about environment, transportation issues, and you are silencing them during the election.

But is there a way to balance this principle of free speech with the need to protect the electoral system from undue corporate financial dominance?

Idealized Corporate Speech vs Reality

Justice Kennedy’s vision of corporate speech reflects an idealized view that resembles classical economic theories, where all actors possess “perfect information” and make rational choices. Kennedy assumes that corporations share useful, specialized knowledge with the public in good faith. However, corporate behavior in politics often prioritizes profit over good information and transparency.

Take Exxon for example:

Exxon was aware of climate change, as early as 1977, 11 years before it became a public issue, according to a recent investigation from InsideClimate News. This knowledge did not prevent the company (now ExxonMobil and the world’s largest oil and gas company) from spending decades refusing to publicly acknowledge climate change and even promoting climate misinformation—an approach many have likened to the lies spread by the tobacco industry regarding the health risks of smoking.

Just as light can be treated as both a wave and a particle, under current law, speech can be treated as both “communication” and “money.” (fact check). Corporations prefer to use the “money” aspect to “donate to”/bribe elected officials rather than engage in accountable public speech. Instead of educating voters through public ads or informative campaigns, large corporations contribute millions to misinformation campaigns and practice divide and rule tactics by hiring consultants to amplify unrelated wedge-issue campaigns on issues like Critical Race Theory or earlier Anti-Gay Marriage campaigns that distract the electorate from the real corporate interests. (fact check)

Proposal: Permit Corporate “Communication”, Forbid “Money” Speech

To reconcile the value of corporate knowledge with the need to limit financial influence, I propose a strict reform: allow large corporations to engage in public communication directly relevant to their area of expertise, but forbid all forms of “money speech”—i.e., significant financial contributions aimed at political influence.

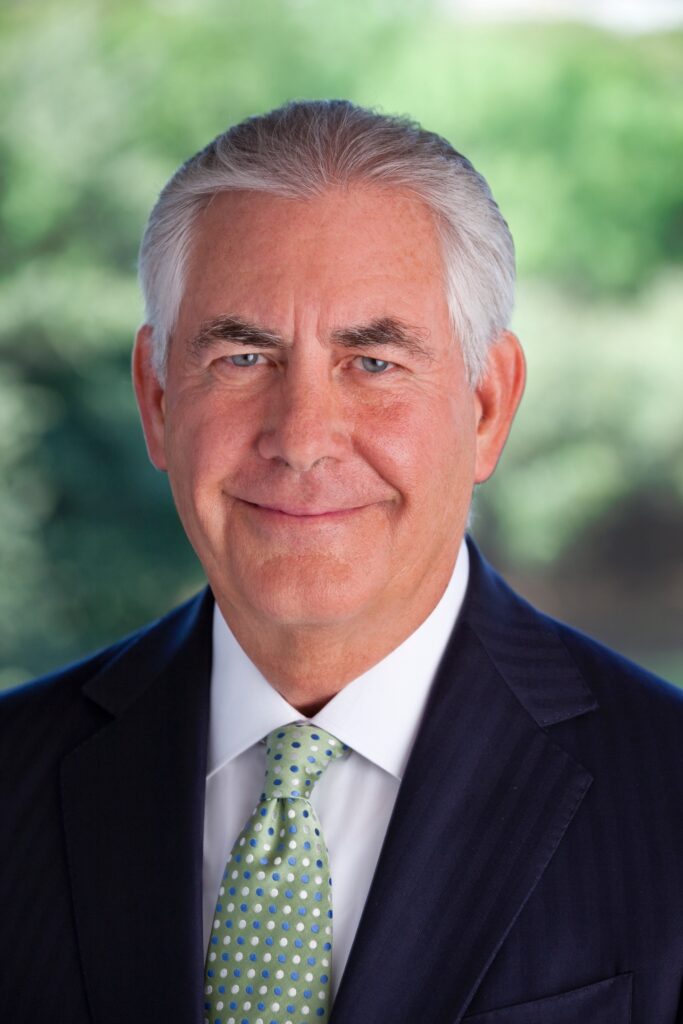

Under this model, large corporations would still be allowed to share information directly relevant to their industry or expertise but would be required to do so transparently. For instance, if ExxonMobil wanted to discuss climate policy publicly, its CEO would need to explicitly approve the message—for example, by stating, “I’m Rex Tillerson, CEO of ExxonMobil, and I approved this message.” This ensures voters know who is behind the message and why, preserving transparency and accountability.

Barring “Money” Speech Entirely

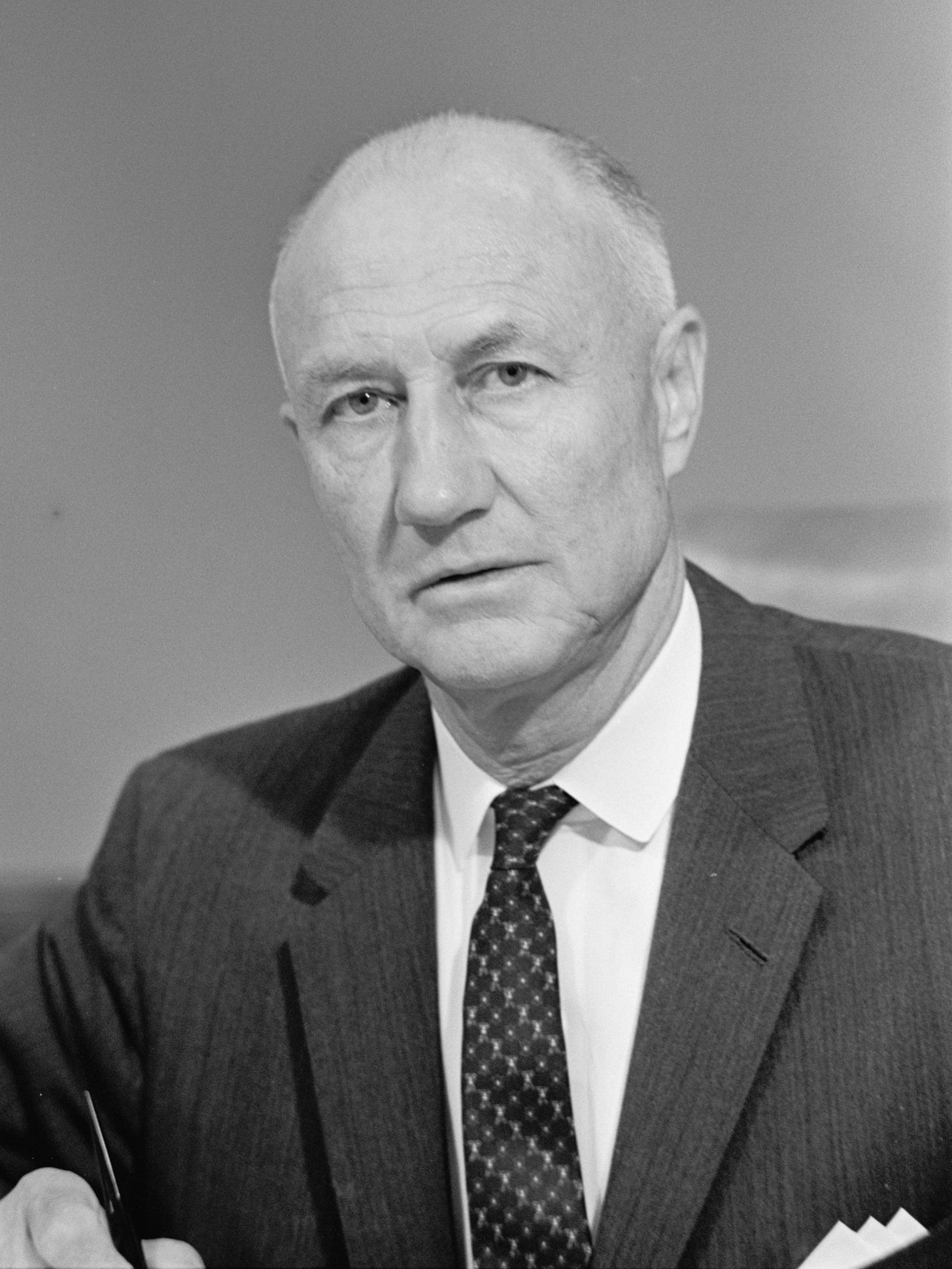

Large corporations, however, would be strictly prohibited from making any direct or indirect financial contributions to candidates, political action committees, or third-party groups. The ban on financial influence would prevent corporations from swaying elections through money while still allowing them a voice in public discourse—albeit one fully transparent and accountable to voters. Small and medium-sized businesses such as Scalia’s local hairdresser the local auto repair shop the the local uh new car dealer

may retain flexibility to combine their efforts in small alliances whose individual disclosure may involve less up-front visibility due to the large number of participants, but large corporations that possess the power to substantially alter political outcomes would have disclosure requirements similar to political candidates.

The “Speaking” Filibuster: Make them Speak

The “speaking filibuster” reform idea offers a useful analogy. In the 1950s, when Senator Strom Thurman wanted to filibuster the 1957 civil rights act, he had to actually take the floor of the Senate and speak continuously in opposition to the bill. Today, however, senators can simply declare a filibuster without speaking or making their filibuster public, which often obstructs legislation in a way that is hidden from public scrutiny.

Similarly, my proposal would end the practice of large corporations’ bad faith claims to want to educate the public (share information) when in fact they prefer to employ money and front groups to sabotage accountable governance. Just as the speaking filibuster holds senators accountable for obstruction, this reform would ensure that corporate influence in politics remains visible, transparent, and limited to public-facing speech.

Restoring Balance in Democracy

In summary, this proposal advocates a two-tiered model of corporate engagement in politics. Large corporations would be permitted to share public information on issues relevant to their expertise, but they would be barred from using financial influence to fund non-transparent speech or donate money to candidates. This approach respects corporate rights to share knowledge while safeguarding the electoral system from the disproportionate influence of money.

Corporate Media has Incentive to Suppress the Issue

One thing not addressed by this proposal, but standing in the way of its passage, is the conflict of interest held by Corporate media. Media companies, especially in swing states like Pennsylvania, where I live, receive substantial revenue from political advertising. This financial incentive may discourage them from covering campaign finance reform, even though polling data shows broad public support for such measures. (fact check)

Though campaign finance reform remains an uphill battle, we cannot resign ourselves to the unchecked corporate influence enabled by errant Supreme Court precedent. Though corporate lawyers and political operatives may fight back initial challenges, we must channel our inevitable short-term defeats into progressive building blocks of change. Only by ensuring that corporations engage transparently in speech while limiting their financial influence, can we restore the power of the electorate and faith in government as a representative of the people.