In this week’s Big Read at the Financial Times, well-known columnist Martin Wolf provides a shotgun-style summary of common objections to 21st-century capitalism. His 2,000-word condemnation of what he calls “Rentier Capitalism” includes almost every popular denouncement of capitalism of recent years and points to all the ways in which the modern world has supposedly let us down.

Most of them are tired clichés and hyperbolic tirades of doubtful accuracy: the unprecedented danger posed to civilized society that is tax havens; the mirage of ever-increasing market concentrations; and of course the perils of wage inequality, without which no condemnation of the era following the great financial crisis would be complete. Not only are financial services in general a parasitic drag on the economy (he literally uses the words “useless” and “unproductive” to describe the financial sector), but their appeal to talented people amounts to an unforgivable brain drain that explains the below-average productivity growth observed in modern Western economies.

Wolf, pouring old wine in new bottles, makes objections as old as economics itself. Even classical economists used to refer to rent extraction — an unfair gain of material resources from the fruits of capitalist development over what would have been required to induce individuals to bring them forth — as “unearned income” with the accompanying moralistic language.

While Wolf mentions some of the well-studied and conventional reasons why the 21st century has seen some of the trends he laments (globalization and superstar effects, the race between technology and education; network effects) he does not advance any reason to doubt those essentially descriptive explanations.

Instead, Wolf resorts to grand, utopian, and moralistic language. He would have us replace “a capitalism rigged to favour a small elite” with one “that gives everybody a justified belief that they can share in the benefits.” Remaining mysteries are who those people doing the rigging really are and why we can’t find the smoking gun of actually “rigging” the economy. In vain I have searched for both.

Especially prominent in Wolf’s text is the differences in earnings between workers and senior management. A particular evil, argues Wolf, is the practice of tying CEO remuneration to share prices, long seen as a successful solution to the principal–agent problem between shareholders and managers. In direct opposition to this Nobel Prize–winning insight, Wolf joins a jolly crowd of dissenters that, among others, includes Matt Yglesias, Paul Krugman, Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, the occasional Economist editorial, and my modestly conspiratorial economics lecturer at University of Glasgow.

Even some market-friendly analysts have argued this point: share-price remuneration creates perverse incentives for managers who’d rather focus on increasing their company’s share price than making truly productive and beneficial investments for their companies. Runaway stock markets are not, mind you, outcomes of money printing, endless rounds of quantitative easing, or any other postcrisis central bank behavior, but due to senior management’s rent-seeking practice of taking up cheap debt to buy back shares in their own company. Let’s explore that a bit more.

Look Further

What all economists must do is work through not only the primary effects of some event, but secondary and often third-order outcomes as well.

As an example, take “job creation” programs, lauded by almost all politicians. By only looking at the number of new jobs in such programs without considering the jobs destroyed by their funding or implementation, you are vastly overstating their real effect. As Bastiat taught us in his famous broken window fallacy, we must ask: what is given up elsewhere so that a desired policy can be realized?

By objecting to share buybacks, Wolf makes such a fallacious argument. His mistake lies in not looking beneath the surface.

What Happens When Companies Buy Back Their Own Shares?

Economics teaches us to think through problems wholly. Rather than accepting naive explanations that quickly come to mind or seem obvious on the surface, economic analysis delves deeper. In opaque and complicated financial systems like ours, a seemingly simple transaction can include countless more, blurring the assessments of what is going on.

With profits (or indeed newly issued debt), companies may buy and retire their own outstanding stock, authorized and managed by senior management whose salaries and bonuses are strictly tied to the company’s stock price. This, of course, looms large in the eyes of left-leaning critics. Share buybacks benefit “shareholders and corporate leadership” rather than their workers, argue Bernie Sanders and Chuck Schumer. Similarly, both Yglesias and Wolf seem to think that management is passing over productive investments and that buybacks add no value, effectively short-changing not only workers but ultimately owners as well, enriching only management.

What share buybacks do is intentionally reduce the outstanding capital of one’s own company. The managers are putting cash behind their conviction that owners can make better use of spare funds than the company can. As Erica York persuasively explains, companies buy back shares when they have “more cash than investment opportunities.”

It may be that the company has enough cash to sustain its current and future operations and is therefore in no need of the extra money. Another possibility is that a company — as most on the left call for governments to do — is taking advantage of low and even negative interest rates, in effect locking in cheap funding for the foreseeable future. When equity is expensive and debt is cheap and plentiful, prudent management should swap one for the other since dividend payments for shareholders come out of corporations’ positive free cash flows anyway. Even if there is something wrong with our extraordinarily low interest rates, it makes perfect sense for long-term business to take advantage of what looks like temporarily cheap funding.

Notice how Wolf’s sleight of hand undermines his argument. He says that share buybacks do not add value to “the company” with the implication that they don’t add value to the economy. The seller — the counterparty to the actual buyback transaction by the company — can either use the proceeds to buy another financial investment or consume them in the real economy. Below we’ll see how that benefits the economy.

Adding Value to the Economy

Monetary economics makes perfectly clear that money spent always goes somewhere. In this case, corporations buying back their own shares transfer funds to sellers of those shares — the funds do not “vaporize.” Wolf and others stop their assessment here and conclude that managers are transferring funds to shareholders in addition to enriching remaining shareholders when the stock price increases.

There are two reasons why the share price ought to rise: First, upon canceling some of the outstanding shares, every remaining share now represents a larger piece of the overall company. As this transaction didn’t change anything about the company’s underlying operations, every share should now be slightly more valuable. Second, if management successfully replaced expensive equity with cheap debt, the company’s effective cost of capital has fallen — making the shares more profitable investments, all things equal (in jargon, while net income falls due to higher interest rate expenses, the return on equity increases as the fewer shares outstanding more than offset the reduction in net income). This is value creation for the company’s shareholders as well as releasing funds for financial markets to profitably invest elsewhere.

Wolf’s failure to look past these initial effects detracts from his argument. A seller of stock now has funds at his disposal for which he has four actions available to him:

- Remain liquid, and so effectively provide reserves to his bank or broker that are used for loans elsewhere or pile up as excess reserves at the Fed.

- Buy another security on the secondary market.

- Invest the funds in an initial public offering (IPO), transferring his funds to a new and thriving business in need of funds.

- Remove the funds from the financial system and consume them.

If the seller remains liquid (1) or buys another security (2), he merely pushes the decision to another person faced with the exact same options. If he invests the funds in an IPO (3), the new company invests the proceeds in its operations. If he spends the proceeds in the real economy (4), they show up as somebody else’s income, add to GDP, and send market signals to entrepreneurs elsewhere in the economy to pivot some investment into these lines of production. However long this round of hot potato is, at the end there is a real transaction.

The financial system is beautiful in that a dozen or more internal transactions, through various routes, ultimately have the same outcome: funds are moved from places where they may not earn very much to where they might. In the share-buyback example that Wolf and others lament, idle cash is moved from a corporation that sees no need for it (or a bank reserve earning interest of excess reserves at the Fed) to fueling startups that do. Share buybacks do not, as Wolf seems to believe, occur “at the expense of corporate investment and so of long-run productivity growth” — that investment just takes place elsewhere.

The hypothetical company’s share buyback merely pushed the decision of what to do with the money to the next person in line — transferred the purchasing power from the company itself to somebody seeing more investment opportunities elsewhere.

It is perfectly possible that nobody in the economy sees any productive investments to make and so share buybacks would ultimately just end up in consumption. That might be a worrying sign and a real instance of secular stagnation. That’s not the argument Wolf makes.

Even if it were, his calls for reinvesting in the company or its workers are misguided. Spending money on new investments that the managers themselves don’t think will pay off seems like a surefire way to perpetuate such dismal productivity growth. If nobody in the entire economy can find profitable investments to make, companies naturally ought to liquidate their holdings and give assets back to their owners for consumption — which is precisely what share buybacks accomplish!

The confused objections to share buybacks illustrate the failure to look past the immediate effect and to understand what financial markets do. In a decentralized way, reacting and incorporating the best available information, they transfer funds from those with money but no ideas to those with ideas but lacking money. Financial markets efficiently allocate capital across the economy, but do so in roundabout ways that are easy to miss.

Looking past the immediate effect allows us to see the bigger picture: share buybacks are one cog in a well-functioning financial system, doing precisely what they are supposed to do. That’s a good thing — not something to lament.

More than Half of All Stock Buybacks are Now Financed by Debt. Here’s Why That’s a Problem

The era of cheap borrowing is fostering corporate America’s favorite investor-pleasing activity: Share buybacks.

Indeed, more than half of all buybacks are now funded by debt. And while there’s an argument that repurchases benefit share prices and investors, at least in the short run, it’s questionable whether highly indebted companies should be doing this. Sort of like mortaging your house to the hilt, then using it to throw a lavish party.

Borrowing oodles of money to buy back shares at the end of an economic cycle, when share prices are near record highs, may seem especially dubious for highly indebted companies like AT&T and American Airlines. Buybacks per se are not inherently wrong-headed, wrote RIA Advisors Chief Investment Strategist Lance Roberts on the Seeking Alpha site, but “when they are coupled with accounting gimmicks and massive levels of debt to fund them … they become problematic.”

Lower interest rates have been a big catalyst for buybacks for years, and further rate reductions can only fuel companies’ urge to gather in even more shares. The Federal Reserve last month decreased its benchmark for short-term rates by a quarter percentage point, and futures markets expect at least two more reductions in 2019. The 10-year U.S. Treasury note, which calls the tune for long-term corporate bonds, yields 1.59% annually, half of what it was last November.

Disturbingly, companies are channeling more cash to investors than they are producing in free cash flow, the first time that has occurred since the Great Recession, according to Goldman Sachs. “Unless earnings growth accelerates materially, companies will likely continue to fund spending by drawing down cash balances and increasing leverage,” wrote David Kostin, Goldman’s chief U.S. strategist, in a note to clients.

Buybacks are a strong catalyst for the bull market. In fact, they are a more significant factor than economic growth, a study last year in the Financial Analysts Journal concluded. The research covered 43 nations over two decades.

Buybacks last year hit a record in the U.S., reaching $806.4 billion for the S&P 500, besting the previous high point of $589.1 billion in 2007, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. Goldman expects them to finish near $1 trillion in 2019. In this year’s first quarter, S&P 500 companies, which cover 80% of U.S. market valuation, bought back $205.1 billion, up 8.8% from the comparable period in 2018.

With fewer of a company’s shares available, the all-important metric of earnings per share swells—to the delight of investors. They’re also happy to receive a bunch of cash for their shares. Plus, a higher EPS, even if artificially enhanced via a buyback, often guides executive compensation.

Why debt dominates

In 2018, according to Yardeni Research, borrowing funded 56% of that year’s record buybacks. Existing corporate cash on the books, of which there is an abundance, is used less often.

Why is this? Ultra-low borrowing costs mean the interest outlay is relatively minuscule, almost a rounding error. As a result, cash can be stockpiled in case it is suddenly needed. And costs are light even for long-term bonds, whose rates the Fed doesn’t control. We’re talking about the 10-year Treasury note, the benchmark for corporations to fix the rates on their own bonds.

In an indirect way, a lower-rate environment is keeping long rates down. Long rates are so low in Europe and Japan, and often negative, that the 10-year T-note is extremely attractive to foreign investors—as is its haven status amid international turmoil, of course. That elevates the price, in turn pulling down the yield. Bond prices and yields move in opposite directions. U.S. corporate bonds respond by lowering their rates.

Further, American companies’ bonds get a tax break on the interest they pay. Not as good as it used to be, yet not bad either. Before the 2017 tax overhaul, they could deduct 100%, but the reform dropped that to a ceiling of 30% of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization).

And there will be an even bigger need for debt to fund repurchasing programs ahead, as corporations’ enormous cash stashes likely will shrink. That’s because, after romping for a long time, earnings growth appears to be on the wane. Earnings typically feed the cash repository. By FactSet’s count, second-quarter S&P 500 earnings dipped 0.7%.

The repurchase reflex

Buybacks are an arena dominated by major companies, many of them long-established tech titans. The top 20 buybacks accounted for 51.2% of the total for the 12 months ending in March, S&P Dow Jones Indices states.

The all-time champ is Apple, which set a quarterly record for repurchases, laying out $23.8 billion in this year’s January-March period. During the past 10 years, it spent $284.3 billion on buybacks. Over the 12 months through March, other voracious buyers were Oracle ($35.3 billion), Cisco Systems ($22.8 billion), Bank of America ($21.5 billion) and Pfizer ($15 billion).

Okay, they have pretty good balance sheets. But what about companies that are heavily debt-laden? Take AT&T, which thanks to its 2018 acquisition of Time Warner, now called WarnerMedia, piled on a dizzying amount of debt. As of the second quarter, long-term debt stands at $159 billion. Nevertheless, Chief Executive Randall Stephenson said on the July 24 earnings call that “we’ll take a hard look at allocating capital to share buybacks in the back half of the year.”

His justification? The company is busy whittling down its debt, having shrunk it $18 billion in the year’s first half, with $12 billion more expected in the second half. Stephenson says debt should be down to 2.5 times EBITDA by year-end, a level that he believes will allow him to prudently repurchase shares. A company spokesperson added that buybacks benefit all shareholders, including the 90% of U.S. employees who own AT&T stock. Trouble is that, according to Goldman, the telecom giant’s Altman Z-Score, which measures credit riskiness, is right now 1.1—which means it is very risky (above 1.8 is in the safe zone). On the other hand, it still is investment grade, rated BBB by Standard & Poor’s.

The same can’t be said for American Airlines Group, which is a junk-rated BB- and has an Altman Z-Score of just 0.8. But the airline, which is buying 50 new planes, is also in the middle of its latest stock buyback program, having spent $1.1 billion of the $2 billion authorized for repurchases. It disbursed $600 million in this year’s first quarter.

The air carrier’s long-term debt stands at $21.2 billion, and net debt is a daunting 4.5 times EBITDA, by Goldman’s measure. A company spokesperson said the company’s priorities are to pay down debt, invest in the business, and return cash to investors. In late 2018, Chief Financial Officer Derek Kerr said that “our stock is under-valued.” Since February 2018, the share price plummeted, losing half its value. The slump likely stems from the global economic slowdown, the trade war and the grounding of the Boeing 737 MAX, analysts say.

But that’s not stopping American and some others, despite their high leverage, from paying investors for their shares. And other than a recession, which generally keelhauls buyback plans, don’t expect companies to ease off their repurchases.

But once a recession inevitably arrives, the result may not be pretty for companies with lots of leverage, in no small part due to buybacks. With corporate debt now higher than its peak in scary late-2008, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan has warned, overly leveraged companies “could amplify the severity of a recession.”

The Stock-Buyback Swindle

American corporations are spending trillions of dollars to repurchase their own stock. The practice is enriching CEOs—at the expense of everyone else.

n the early 1980s, a group of menacing outsiders arrived at the gates of American corporations. The “raiders,” as these outsiders were called, were crude in method and purpose. After buying up controlling shares in a corporation, they aimed to extract a quick profit by dethroning its “underperforming” CEO and selling off its assets. Managers—many of whom, to be fair, had grown complacent—rushed to protect their institutions, crafting new defensive measures and lodging appeals in state courts. In the end, the raiders were driven off and their moneyman, Michael Milken, was thrown in prison. Thus ended a colorful chapter in American business history.

Or so it seemed. Today, another effort is under way to raid corporate assets at the expense of employees, investors, and taxpayers. But this time, the attack isn’t coming from the outside. It’s coming from inside the citadel, perpetrated by the very chieftains who are supposed to protect the place. And it’s happening under the most innocuous of names: stock buybacks.

You’ve seen the phrase. It glazes the eyes, numbs the soul, makes you wonder what’s for dinner. The practice sounds deeply normal, like the regularly scheduled maintenance on your car.

It is anything but normal. Before the 1980s, corporations rarely repurchased shares of their own stock. When they started to, it was typically a defensive move intended to fend off raiders, who were drawn to cash piles on a company’s balance sheet. By contrast, according to Federal Reserve data compiled by Goldman Sachs, over the past nine years, corporations have put more money into their own stocks—an astonishing $3.8 trillion—than every other type of investor (individuals, mutual funds, pension funds, foreign investors) combined. Corporations describe the practice as an efficient way to return money to shareholders. By reducing the number of shares outstanding in the market, a buyback lifts the price of each remaining share. But that spike is often short-lived: A study by the research firm Fortuna Advisors found that, five years out, the stocks of companies that engaged in heavy buybacks performed worse for shareholders than the stocks of companies that didn’t.

One class of shareholder, however, has benefited greatly from the temporary price jumps: the managers who initiate buybacks and are privy to their exact scope and timing. Last year, SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson Jr. instructed his staff to “take a look at how buybacks affect how much skin executives keep in the game.” This analysis revealed that in the eight days following a buyback announcement, executives on average sold five times as much stock as they had on an ordinary day. “Thus,” Jackson said, “executives personally capture the benefit of the short-term stock-price pop created by the buyback announcement.”

This extractive behavior has rightly been decried for worsening income inequality. Some politicians on the left—Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Chuck Schumer—have lately gotten around to opposing buybacks on these grounds. But even the staunchest free-market capitalist should be concerned, too. The proliferation of stock buybacks is more than just another way of feathering executives’ nests. By systematically draining capital from America’s public companies, the habit threatens the competitive prospects of American industry—and corrupts the underpinnings of corporate capitalism itself.

The rise of the stock buyback began during the heyday of corporate raiders. In the early 1980s, an economist named Michael C. Jensen presented a paper titled “Reflections on the Corporation as a Social Invention.” It attacked the conception of corporations that had prevailed since roughly the 1920s—that they existed to serve a variety of constituencies, including employees, customers, stockholders, and even the public interest. Instead, Jensen asserted a new ideology that would become known as “shareholder value.” Corporate managers had one job, and one job alone: to increase the short-term share price of the firm.

The philosophy had immediate appeal to the raiders, who used it to give their depredations a fig leaf of legitimacy. And though the raiders were eventually turned back, the idea of shareholder value proved harder to dispel. To ward off hostile takeovers, boards started firing CEOs who didn’t deliver near-term stock-price gains. The rolling of a few big heads—including General Motors’ Robert Stempel in 1992 and IBM’s John Akers in 1993—drove home the point to CEOs: They had better start thinking about shareholder value. If their conversion to the enemy faith was at first grudging, CEOs soon found a reason to love it. One of the main tenets of shareholder value is that managers’ interests should be aligned with shareholders’ interests. To accomplish this goal, boards began granting CEOs large blocks of company stock and stock options.

The shift in compensation was intended to encourage CEOs to maximize returns for shareholders. In practice, something else happened. The rise of stock incentives coincided with a loosening of SEC rules governing stock buybacks. Three times before (in 1967, ’70, and ’73), the agency had considered such a rule change, and each time it had deemed the dangers of insider “market manipulation” too great. It relented just before CEOs began acquiring ever greater portfolios of their own corporate stock, making such manipulation that much more tantalizing.

Too tantalizing for CEOs to resist. Today, the abuse of stock buybacks is so widespread that naming abusers is a bit like singling out snowflakes for ruining the driveway. But somebody needs to be called out.

So take Craig Menear, the chairman and CEO of Home Depot. On a conference call with investors in February 2018, he and his team mentioned their “plan to repurchase approximately $4 billion of outstanding shares during the year.” The next day, he sold 113,687 shares, netting $18 million.* The following day, he was granted 38,689 new shares, and promptly unloaded 24,286 shares for a profit of $4.5 million. Though Menear’s stated compensation in SEC filings was $11.4 million for 2018, stock sales helped him earn an additional $30 million for the year.

By contrast, the median worker pay at Home Depot is $23,000 a year. If the money spent on buybacks had been used to boost salaries, the Roosevelt Institute and the National Employment Law Project calculated, each worker would have made an additional $18,000 a year. But buybacks are more than just unfair. They’re myopic. Amazon (which hasn’t repurchased a share in seven years) is presently making the sort of investments in people, technology, and products that could eventually make Home Depot irrelevant. When that happens, Home Depot will probably wish it hadn’t spent all those billions to buy back 35 percent of its shares. “When you’ve got a mature company, when everything seems to be going smoothly, that’s the exact moment you need to start worrying Jeff Bezos is going to start eating your lunch,” the shareholder activist Nell Minow told me.

Then there’s Merck. The pharmaceutical company was a paragon of corporate excellence through the second half of the 20th century. “Medicine is for people, not for profits,” George Merck II declared on the cover of Time in 1952. “And if we have remembered that, the profits have never failed to appear.” In the late 1980s, then-CEO Roy Vagelos, rather than sit on a drug that could cure river blindness in Africa but that no one could pay for, persuaded his board of directors to manufacture and distribute the drug for free—which, as Vagelos later noted in his memoir, cost the company more than $200 million. More recently, Merck has been using its massive earnings (its net income for 2018 was $6.2 billion) to repurchase shares of its own stock. A study by the economists William Lazonick and Öner Tulum showed that from 2008 to 2017 the company distributed 133 percent of its profits, through buybacks and dividends, to shareholders—including CEO Kenneth Frazier, who has sold $54.8 million in stock since last July. How is this sustainable? “It’s not,” Lazonick says. Merck insists it must keep drug prices high to fund new research. In 2018, the company spent $10 billion on R&D—and $14 billion on share repurchases and dividends. Finally, consider the executives at Applied Materials, a maker of semiconductor-manufacturing equipment. As is the case at many companies, its CEO receives incentive pay based on certain metrics. One is earnings per share, or EPS, a widely used barometer of corporate performance. Normally, EPS is lifted by improving earnings. But EPS can be easily manipulated through a stock buyback, which simply reduces the denominator—the number of outstanding shares. At Applied Materials, earnings declined 3.5 percent last year. Yet the company still managed to eke out EPS growth of 1.9 percent. How? In part, by taking more than 10 percent of its shares off the market via buybacks. That move helped executives unlock more incentive compensation—which, these days, usually comes in the form of stock or stock options.

Corporations offer a variety of justifications for the practice of repurchasing stock. One is that buybacks are a more “flexible” way of returning money to shareholders than dividends, which (it’s true) once raised are very hard to reduce. Another argument: Some companies just make more money than they can possibly put to good use. This likewise has a smidgen of truth. Apple may not have $1 billion worth of good bets to make or companies it wants to acquire. Though, if this were the real reason companies are repurchasing stock, it would imply that biotechnology, banking, and big retail—sectors that hold some of the biggest practitioners of buybacks—are nearing a dead end, idea-wise. CEOs will also sometimes make the case that their stock is undervalued, and that repurchases represent an opportunity to buy low. But in reality, notes Fortuna’s Gregory Milano, companies tend to buy their stock high, when they’re flush with cash. The 10th year of a bull market is hardly a time for bargain-hunting.

Capitalism takes many forms. But the variant that propelled America through the 20th century was, at its heart, a means of pooling resources toward a common endeavor, whether that was building railroads, developing new drugs, or making microwave ovens. There used to be a healthy debate about which of their stakeholders corporations ought to serve—employees, stockholders, customers—and in what order. But no one, not even Michael Jensen, ever suggested that a corporation should exist solely to serve the interests of the people entrusted to run it.

Many early stock certificates bore an image—a factory, a car, a canal—representing the purpose of the corporation that issued them. It was a reminder that the financial instrument was being put to productive use. Corporations that plow their profits into buybacks would be hard-pressed to put an image on their stock certificate today, other than, perhaps, the visage of their CEO.

Raoul Pal’s Thesis: The “Doom Loop”

Raoul Pal is a former hedge fund manager who retired at age 36 but remains actively involved in the world of macroeconomics and finance. In recent years, he started a finance news and content service called Real Vision.

In a video posted on YouTube on August 14th, Pal discusses his case for a recession in the next year or so as well as a very alarming scenario he calls the “doom loop.” It’s a fascinating and frightening thesis, and I find it persuasive. Here’s the line of reasoning:

(1) The Fed lowers interest rates to stimulate the economy through increased lending. How else are lower interest rates supposed to stimulate anything besides through more lending, i.e. more debt?

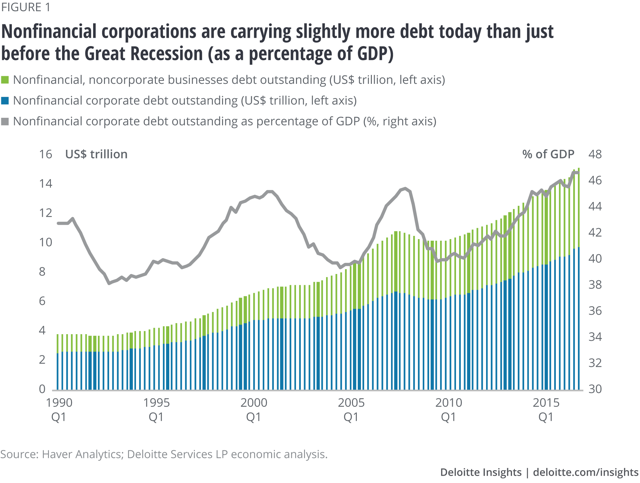

(2) As a result, all sorts of market and government actors increase their debt loads. Corporations, especially, took advantage of falling rates to refinance and take on more debt.

Source: Deloitte

(3) Some of this debt buildup has been for acquisitions or mega-mergers, but much of it was taken on simply for share buybacks. See, for instance, this chart showing the way in which debt issuance and share buybacks became tightly correlated right around the time that the Fed Funds rate bottomed near zero. (See my article addressing this subject here.)

Source: Hussman Funds

Debt-funded buybacks have served as a convenient way for corporate executives to lift earnings per share, thus meeting guidance more regularly and reaching the targets for their performance bonuses more often. (I wrote about this subject here.) What’s more, an SEC study found that insider selling tended to coincide with the announcements or implementation of buybacks.

(4) Indeed, if you look at the performance of U.S. stocks versus any other country or world region’s stocks, you’ll notice a stark difference. U.S. stocks have soared ahead of the competition. It turns out that this is largely because of buybacks, as corporations themselves have been the biggest net buyers of corporate stock since the Great Recession:

Source: Avondale Partners

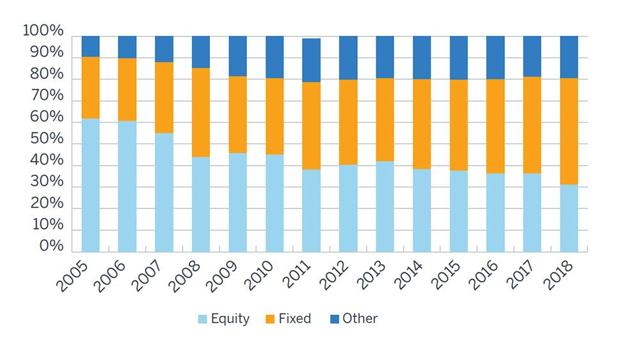

Notice that institutions (including pension funds) have been net sellers of U.S. equities since the recession. This likely means that pensions have been forced to sell many of their assets to fund benefit payouts but have sold other assets such as Treasuries at a faster rate than equities.

(5) Who is buying all this debt being issued to fund buybacks? The answer, in large part, is pensions. Mainly corporate pensions:

Writes Mark Johnson: “This uptick in bond buying has caused corporate pension funds to play a more influential role in the bond market, since pension managers tend to hold bonds for the long term. As more and more companies adopt the strategy of buying more bonds, pension demand could total $150 billion a year. It is estimated that corporate pension funds buy more than 50 percent of new long-term bonds, up from an estimated 25 percent a few years ago.”

So corporate pensions are buying more and more bonds. Which bonds? Specifically, corporate bonds: “Pension plans… like to use corporate bonds to hedge liabilities.” Corporate bonds offer the highest yields. Of course, pensions are only allowed to own investment grade corporate debt, but if they opt for longer duration or lower rated bonds they can get a higher yield. In the previous twelve months, BBB-rated corporate bonds have yielded as high as 4.83%, certainly better than the highest yield offered by the 20-year Treasury bill in the last twelve months — 3.27%.

BBB-rated corporate debt has grown to be roughly half of all corporate debt outstanding. That’s one (small, for some companies) step above junk status.

(6) During a recession, much of this investment grade debt (Pal guesstimates 10-20%) will be downgraded. But remember: pensions cannot own junk bonds. If BBB-rated debt on their books gets downgraded, they will be forced to sell it, even at a loss. If multiple downgrades happen quickly in succession, the supply of newly labeled junk bonds will overwhelm demand from other market buyers of those debt instruments. This could lead to a fire sale scenario, in which the prices of junk bonds plunge as pensions dump huge supplies into an unsuspecting market.

(7) Not only would pensions have to accept a fraction of their cost basis for these former investment grade bonds, they would also see their primary revenue stream — tax revenue — slacken during a recession. Tax receipts, after all, are as cyclical as the business cycle. When individuals and businesses aren’t making as much money, there is less available to be taxed. This would diminish demand for corporate bonds, which would cause corporate bond yields to spike.

(8) All of this chaos in the credit markets will make it very difficult for corporations to issue debt at anything other than high rates. This will cause the costs of new debt to soar high enough for buybacks to become prohibitively expensive. Moreover, cash flows will dry up, as they do in every recession, and thus every potential source of funds to use for buybacks will disappear.

Therefore…

(9) If the previous points play out, the biggest net buyer of U.S. equities over the last ten years will no longer be a buyer. “The largest buyer will have left the room,” as Pal says. In fact, publicly traded corporations may actually be net issuers of shares during the next recession as they were in 2008-2009.

In the words of Jesse Colombo, “If the stock market performed as poorly as it did in 2018 with record amounts of buybacks to prop it up, just imagine how much worse it would be if buybacks were to slow down significantly or grind to a halt?”

I don’t see how the preceding chain of events playing out as described would not ultimately result in a very nasty stock market crash. Whether it’s a relatively quick crash like in 2008-2009 or a bit more drawn out like from 2001-2003 is unknown. Either way, I see the above scenario as plausible. Disturbingly so.

Since I’m an income-oriented investor, my preferred method of hedging against this possible crash scenario is to hold ample cash and ultra-short term bond funds. That way, if this scenario does play out, I will be prepared to buy assets at fire sale prices with yields higher than I might ever see again in my lifetime.

Raoul Pal’s thesis is fascinating, but it could be wrong. What I’m much more certain of is that the Fed bears the majority of the blame for the underfunding of pensions and thus for putting us into a situation in which Pal’s thesis would even be possible.