In Jan 1975, Commentary Magazine argued that the US should threaten to invade the Persian Gulf if they did not:

- agree to price oil exclusively in dollars, thereby generating demand for dollars

- save oil profits in US Treasury bills, thereby financing the US debt

- buy American weapons, including surplus Vietnam war equipment, and future US weapons, thereby financing the military industrial complex

There remains the argument that military intervention in the Persian Gulf would on moral grounds alone not be countenanced by domestic public opinion. Nor is it only the public that would presumably find in the act a manifestation of complete moral bankruptcy. One has the distinct impression that the foreign-policy elite shares this view and that in the certitude with which the public’s supposed reaction is diagnosed there is something close to a wish-fulfilling prophecy. It is a curious reaction coming from those who once found no great difficulty, moral or otherwise, in supporting the intervention in Vietnam or who, in finally abandoning their support for intervention, did so not on moral grounds, but because they concluded Vietnam could not have a successful outcome or that, whatever the outcome, the costs had become disproportionate to the interests at stake. Perhaps their present reaction to the prospect of armed intervention in the Persian Gulf is not so curious, though, given this record. It is not surprising that, having lacked a sense of balance, moral and otherwise, in that most painful experience, they should lack a sense of balance today, and that we should find the law of compensation—or rather of overcompensation—at work.

At issue here is not whether there is some clear moral or legal basis for justifying armed intervention in the Persian Gulf, but whether public opinion would be morally outraged by the action. Though it is not uncommon to find them confused, these are two quite different questions. There is no need for positive moral approval, let alone moral fervor, by the public so long as it consents to the need for the action. There may even be considerable gain in the absence of that element which has so often attended policy in the past. The difficulty, of course, is that the public has been long habituated to support the use of force only in cases which have been made to appear as necessary for the containment of Communism, in turn equated with the nation’s security. Could the public be induced, in the shadow of Vietnam, to support a military intervention that bore no apparent or tangible relation to the containment of Communism, itself a factor of diminishing importance in determining the public’s disposition? No one can say. Put in the abstract, the question itself may be rather meaningless. It would take on meaning only after a concerted effort had been made to persuade the public that the alternatives to intervention were laden with dangers to the nation’s well-being. Even then it remains an open question whether an administration could obtain public support, or tolerance, for intervention in the absence of events at home that, once plainly visible, would require little further effort in persuasion. In this instance, the choice might well be between a public that would oppose intervention so long as the interests at stake were not clear, and could not readily be made clear, and a public that would support intervention only when these interests had unfortunately become only too clear.

The point is worth emphasis that we simply do not know what might bring the public to support intervention in the Persian Gulf. If the public viewed such intervention as another Vietnam, they would most assuredly oppose it. But if intervention were to promise success at relatively modest cost, opinion might well move in the direction of support, and particularly if unemployment were to rise to 8 or 9 per cent. Moreover, in this instance, by contrast to Vietnam, the existence of an all-volunteer military force would preclude the painful issues once raised by the draft. Nor is it at all clear that the Left would take the same position toward intervention in the present case as it did toward Vietnam. For the effects of the current oil price on many poor countries do not endear the major oil producers to much of the Left. The relative ease with which Vietnam could be depicted as an attempt to preserve American domination over the developing states, a domination alleged to serve only American interests, would be difficult to repeat today, and this despite the inadequately perceived effects of the oil crisis.

UNDERSTANDING PETRODOLLAR: US DOLLAR, OIL PRICES & SAUDI ARABIA (EITS #5)

08:32

To overcome the gridlock, the US sought to apply pressure on Saudi Arabia by openly discussing the military option of occupying Saudi Arabia. On 1 January 1975, Commentary magazine published

08:45

one of the most famous articles in the history of American foreign policy.

08:50

The article was written by Robert W. Tucker, head of the American Foreign Policy Institute

08:55

and a member of the inner circle of the White House. The title was “Oil: The Issue of American Intervention” and it made explicit references to the military scenario the US was working on. The article served its purpose and convinced

09:11

the Saudis to sign the deal. Despite a range of highs and lows, all administrations

09:19

ever since President Carter have shown commitment to the ma ntra of a “strong dollar.” For 35

09:25

years, from 1975 to 2010, the Petrodollar deal has remained intact, despite oil price

09:32

increases and dollar volatility. The dollar has solidified its role as the leading reserve

09:37

currency and the leading payments currency. By 2009, a new economic crisis eroded the

09:45

stability of the Petrodollar deal. In September of the same year, world leaders gathered for

09:51

the G20 Leaders’ Summit and President Obama proposed a plan to boost world growth based

09:57

on a simple idea: Each major economic block or region would commit to move away from a

10:03

sector it has over-relied and toward an area that offered growth potential.

10:08

For China and Japan, this would mean moving from capital investment to consumption. Europe

10:13

would move from exports to investment and the US itself would take on the task of increasing

10:19

exports. The main obstacle in attaining a growth in

10:22

export was that without being able to double the size of labour force or the productivity

10:27

of labour (the main drivers of industrial production growth), the only viable option

10:32

would be to cheapen the currency. By July 2011, just 18 months after the meeting,

10:39

the dollar index stood at 80.48, which represented a decline of 8% and a new all-time low. A currency war had started which continues to survive until today.

10:52

Relations between Saudi Arabia and the US have deteriorated sharply over the course

10:56

of the Obama administration. There are a number of causes:

11:01

* The Iran-US nuclear negotiations and the US acknowledgment of Iran as the leading regional

11:06

power. * The release of a top-secret 28-page section

11:10

of the 9/11 Commission Report that clearly reveals links between members of the Saudi

11:15

royal family and the 9/11 hijackers. The Saudis have threatened to sell their US Treasury

11:20

securities in response but they have so far failed to keep their word.

11:25

* The US is now a net exporter of energy, and supposedly, has the largest oil reserves

11:31

in the world

11:32

In response to the weakening of the US dollar, several OPEC nations are allowing oil transactions

11:38

to be carried out in other currencies:

11:41

* In January 2016, India and Iran agreed to settle their oil sales in Indian rupees.

11:47

* In 2014, Qatar agreed with China to be the first hub for clearing transactions in the

11:52

Chinese yuan. * In December 2015, the United Arab Emirates

11:56

(UAE) and China created a new currency swap agreement for the yuan.

12:00

All the above strongly indicate that the Gulf States are taking measures to reduce their

12:04

dependence and exposure to the US dollar. All of the conditions that gave rise to the

12:10

Petrodollar agreement now stand in the exact opposite position of where they were in 1975.

12:16

Neither the US nor Saudi Arabia have much leverage over the other.

12:20

A new oil pricing mechanism is possible, and once identified and announced, it will signify

12:26

the end of the US dollar as the leading currency. The oil price will pave the way and will certainly

12:32

soon be followed by other goods and commodities. Will this be the start

13:29

of a new era?

Trump SELLS OUT American Troops

“He sells troops. “We have a very good relationship with Saudi Arabia—I said, listen, you’re a very rich country. You want more troops? I’m going to send them to you, but you’ve got to pay us. They’re paying us. They’ve already deposited $1B in the bank.””

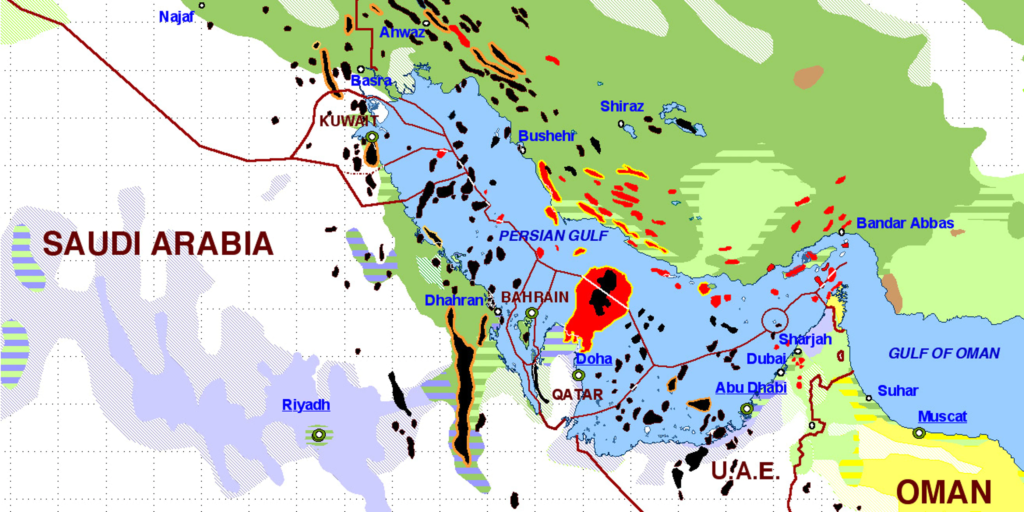

One Map That Explains the Dangerous Saudi-Iranian Conflict

What the map shows is that, due to a peculiar correlation of religious history and anaerobic decomposition of plankton, almost all the Persian Gulf’s fossil fuels are located underneath Shiites. This is true even in Sunni Saudi Arabia, where the major oil fields are in the Eastern Province, which has a majority Shiite population.

As a result, one of the Saudi royal family’s deepest fears is that one day Saudi Shiites will secede, with their oil, and ally with Shiite Iran.

.. Similar calculations were behind George H.W. Bush’s decision to stand by while Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons in 1991 to put down an insurrection by Iraqi Shiites at the end of the Gulf War. As New York Timescolumnist Thomas Friedman explained at the time, Saddam had “held Iraq together, much to the satisfaction of the American allies Turkey and Saudi Arabia.”