Every few months, a prominent person or publication points out that McDonalds workers in Denmark receive $22 per hour, 6 weeks of vacation, and sick pay. This compensation comes on top of the general slate of social benefits in Denmark, which includes child allowances, health care, child care, paid leave, retirement, and education through college, among other things.

In these discussions, relatively little is said about how this all came to be. This is sad because it’s a good story and because the story provides a good window into why Nordic labor markets are the way they are.

McDonalds opened its first store in Denmark in 1981. At that point, it was operating in over 20 countries and had successfully avoided unions in all but one, Sweden.

When McDonalds arrived in Denmark, the labor market was governed by a set of sectoral labor agreements that established the wages and conditions for all the workers in a given sector. Under the prevailing norms, McDonalds should have adhered to the hotel and restaurant union agreement. But they didn’t have to do so, legally speaking. The union agreement is not binding on sector employers in the same way that a contract is. You can’t sue a company for ignoring it. It is strictly “voluntary.”

McDonalds decided not to follow the union agreement and thus set up its own pay levels and work rules instead. This was a departure, not just from what Danish companies did, but even from what other similar foreign companies did. For example, Burger King, which is identical to McDonalds in all relevant respects, decided to follow the union agreement when it came to Denmark a few years earlier.

Naturally, this decision from McDonalds drew the attention of the Danish labor movement. According to the press reports, the struggle to get McDonalds to follow the hotel and restaurant workers agreement began in 1982, but the efforts were very slow at first. McDonalds maintained that it had a principled position against unions and negotiations and press overtures were unable to move them off that position.

In late 1988 and early 1989, the unions decided enough was enough and called sympathy strikes in adjacent industries in order to cripple McDonalds operations. Sixteen different sector unions participated in the sympathy strikes.

Dockworkers refused to unload containers that had McDonalds equipment in them. Printers refused to supply printed materials to the stores, such as menus and cups. Construction workers refused to build McDonalds stores and even stopped construction on a store that was already in progress but not yet complete. The typographers union refused to place McDonalds advertisements in publications, which eliminated the company’s print advertisement presence. Truckers refused to deliver food and beer to McDonalds. Food and beverage workers that worked at facilities that prepared food for the stores refused to work on McDonalds products.

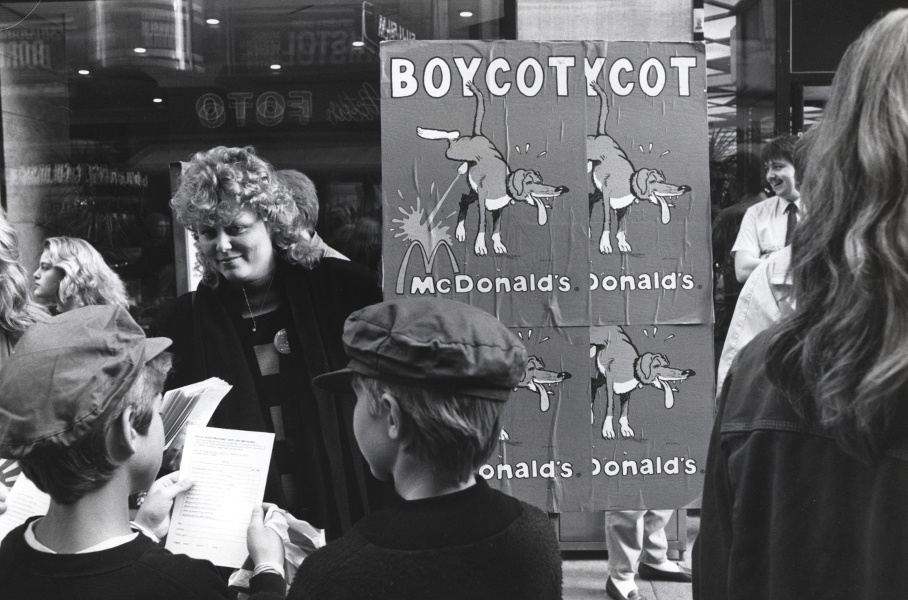

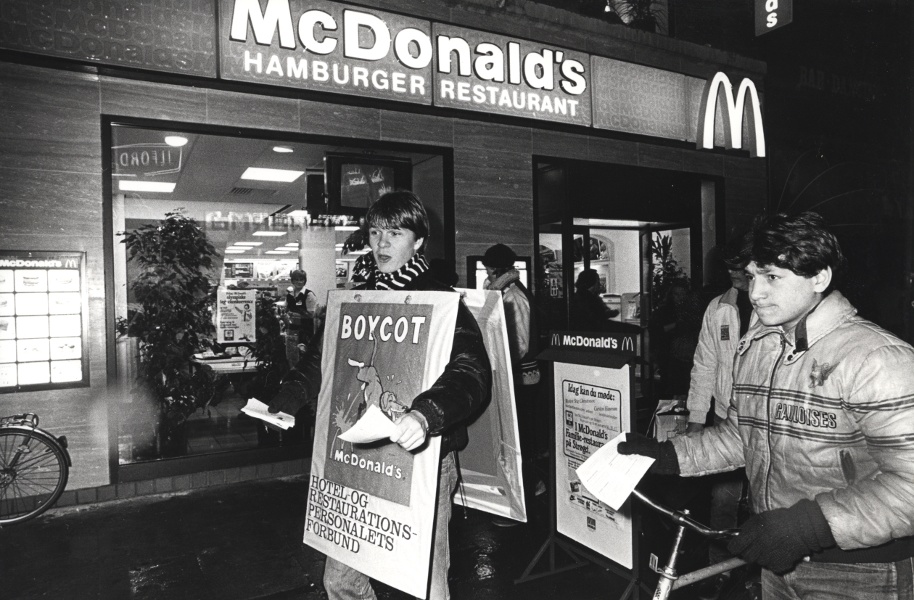

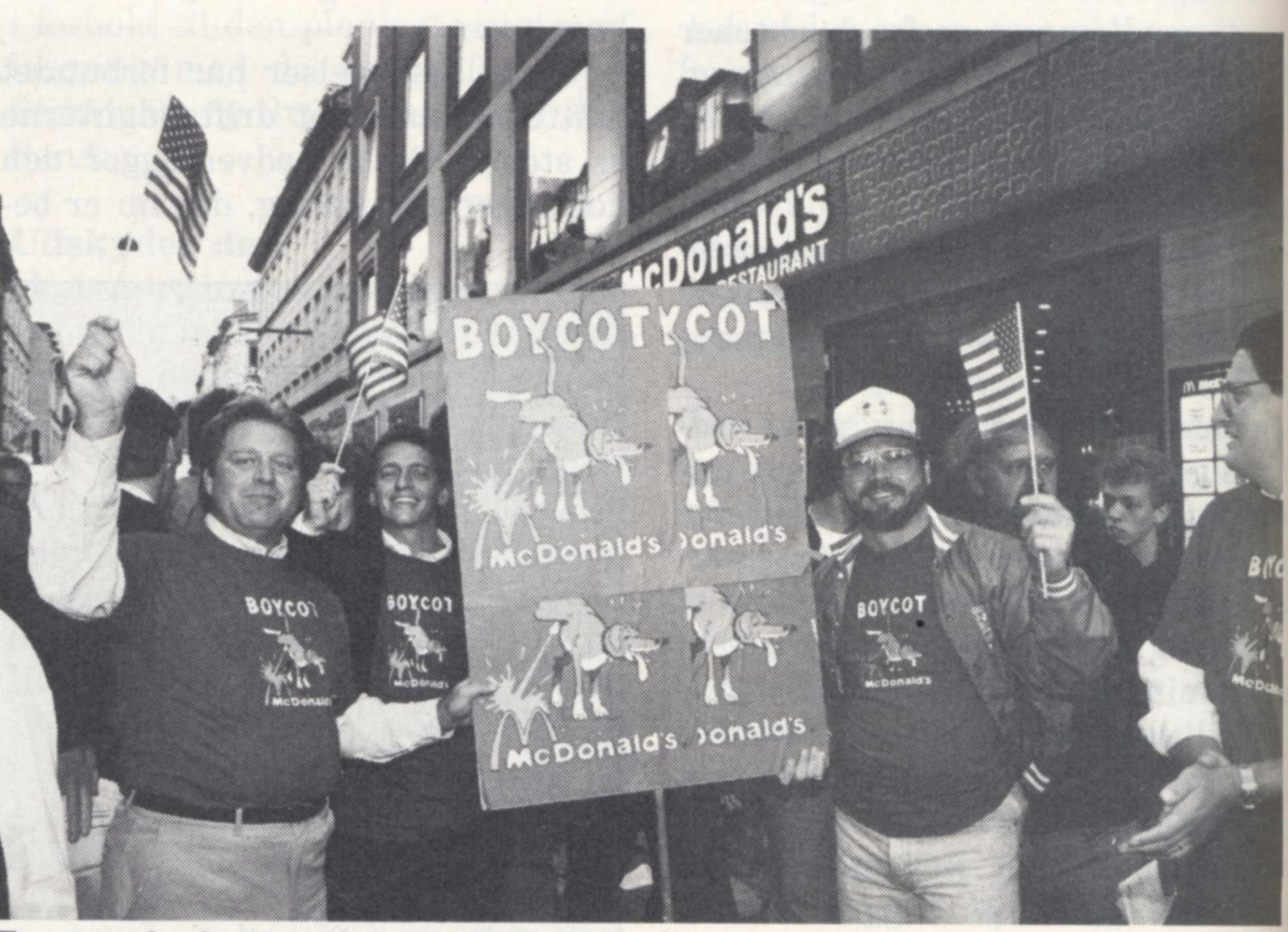

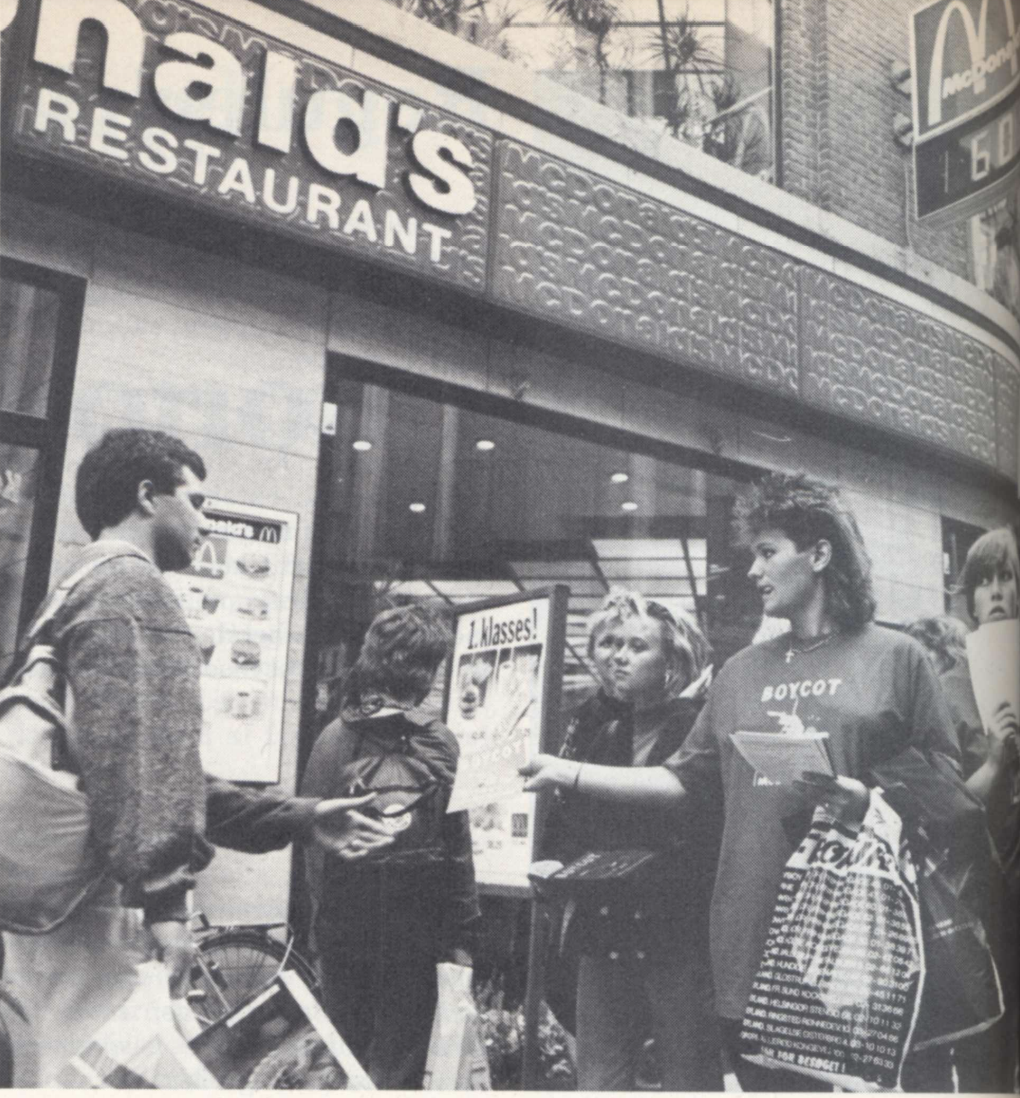

In addition to wreaking havoc on McDonalds supply chains, the unions engaged in picketing and leaflet campaigns in front of McDonalds locations, urging consumers to boycott the company.

Once the sympathy strikes got going, McDonalds folded pretty quickly and decided to start following the hotel and restaurant agreement in 1989.

This is why McDonalds workers in Denmark are paid $22 per hour.

I bring this up because people say a lot of things about the economies of the Nordic countries and why they are so much more equal than ours. In this discussion, certainly the presence of unions and sector bargaining comes up, but rarely do you get a discussion of just how radically powerful and organized the Nordic unions are and have been. If you didn’t know better, you’d think the Nordic labor market is the way it is because all of the employers and workers came together and agreed that their system is better for everyone. And while it’s true of course that, on a day-to-day basis, labor relations in the countries are peaceful, lurking behind that peace is often a credible threat that the unions will crush an employer that steps out of line, not just by striking at one site or at one company, but by striking every single thing that the company touches.

President Trump Eyes a New Real-Estate Purchase: Greenland

In conversations with aides, the president has—with varying degrees of seriousness—floated the idea of the U.S. buying the autonomous Danish territory

President Trump made his name on the world’s most famous island. Now he wants to buy the world’s biggest.

The idea of the U.S. purchasing Greenland has captured the former real-estate developer’s imagination, according to people familiar with the discussion, who said Mr. Trump has, with varying degrees of seriousness, repeatedly expressed interest in buying the ice-covered autonomous Danish territory between the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans.

In meetings, at dinners and in passing conversations, Mr. Trump has asked advisers whether the U.S. can acquire Greenland, listened with interest when they discuss its abundant resources and geopolitical importance and, according to two of the people, has asked his White House counsel to look into the idea.

Some of his advisers have supported the concept, saying it would be a good economic play, two of the people said, while others dismissed it as a fleeting fascination that will never come to fruition. It is also unclear how the U.S. would go about acquiring Greenland even if the effort were serious.

With a population of about 56,000, Greenland is a self-ruling part of the Kingdom of Denmark, and while its government decides on most domestic matters, foreign and security policy is handled by Copenhagen. Mr. Trump is scheduled to make his first visit to Denmark early next month, although the visit is unrelated, these people said.

Are the Danes Melancholy? Are the Swedes Sad?

That lower G.D.P. number conceals two important points. First, by any measure people in the lower part of the income distribution are much better off in Nordic societies than their U.S. counterparts. That is, there is a lot less misery in Scandinavia — and because everyone has some chance of falling into low income, this reduces the risk of misery for a much larger share of the population

Second, much of the gap in real G.D.P. represents a choice, not a cost. Nordic workers have much more vacation, much more time for family and leisure, than their counterparts in our “no vacation nation.”

.. They aren’t “socialist,” if that means government control of the means of production. They are, however, quite strongly social-democratic: as Exhibit 1 shows, they have high taxes, which finance much more generous social benefits than we have here. They also have policies on wages, working hours, and more that tilt the balance toward workers in a number of dimensions.

.. Clearly, the Nordic economies are better for lower-income families — roughly the bottom 30 percent of the population.

.. But this understates the case, because these data don’t include “in kind” benefits like health care and education. All of the Nordic countries have universal health care — not just single-payer, but for the most part direct government provision (a.k.a. “socialized medicine.”)

Nordic education also lacks the glaring inequality in quality all too characteristic of the U.S. system.

.. Once you take these benefits into account, it’s likely that at least half the Nordic population are better off materially than their U.S. counterparts. But what about the upper half?

.. a large part of the difference — in the case of Denmark, more than all of it — comes from a lower number of hours worked annually per worker. This does not reflect mass underemployment. Instead, it reflects policy: all of the Nordic countries require that employers give workers a minimum of 25 days of paid vacation every year, while the U.S. has no leave policy at all.

.. Once you take vacations into account, Denmark and Sweden basically look comparable in performance to the U.S.

.. The point for welfare comparisons is that while Nordic families at, say, the 60th percentile of the income distribution have lower purchasing power than their American counterparts, they also have much more free time and an arguably better work-life balance. Are they really worse off? You can make a good case that taking all of this into account, the majority of Nordic citizens are actually better off than Americans.

.. The O.E.C.D. publishes measures of self-reported “life satisfaction”; all of the Nordic nations rank above the U.S. Objective measures like life expectancy and mortality rates are also much better in Scandinavia.

Notes on a Butter Republic

for decades the right has tried to shout down any attempt to sand down some of the rough edges of capitalism, whether through health guarantees, income supports, or anything else, by yelling “socialism.” Sooner or later people were bound to say that if any attempt to make our system less harsh is socialism, well, they’re socialists.

.. The truth is that there are hardly any people in the U.S. who want the government to seize the means of production, or even the economy’s commanding heights. What they want is social democracy – the kinds of basic guarantees of health care, protection against poverty, etc., that almost every other advanced country provides.

.. Denmark, where tax receipts are 46 percent of GDP compared with 26 percent in the U.S., is arguably the most social-democratic country in the world.

.. According to conservative doctrine, the combination of high taxes and aid to “takers” must really destroy incentives both to create jobs and to take them in any case. So Denmark must suffer from mass unemployment, right?